CASE REPORT

Management of large post-crossover inguinal lymphocele

Nair MD,1 Pisano U,2 Philippou M,2 Byrne D1

Abstract

A 73-year-old man with a history of peripheral arterial disease and previous bilateral common femoral artery reconstruction presented with left foot critical limb-threatening ischaemia and underwent right to left femoro-profunda crossover grafting. Postoperatively, he developed a left groin lymph leak that initially dried up but later re-presented as a very large lymphocele. Initial attempts with aspiration on three occasions and then surgical drainage with sac excision and ligation of long saphenous lymphatics did not lead to resolution. Subsequently, a hybrid approach using percutaneous lymphangiography and drainage, sclerotherapy (bleomycin, then absolute alcohol) and eventual identification and ligation of the afferent lymphatic channel resulted in resolution of the lymphocele without untoward side effects, sepsis or compromise of the revascularisation.

Background

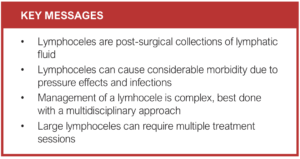

Postoperative fluid collections after groin vascular surgery can commonly include seromas, haematomas, lymphoceles and abscesses. Lymphoceles are abnormal lymphatic fluid collections without epithelial lining that form as a result of disruption of lymphatic channels during surgical procedures. They can result in considerable morbidity with significant swelling, pain, sepsis and failure of revascularisation.

Management strategies include conservative, aspiration, surgical drainage with or without sac excision and ligation of lymphatics, and the use of sclerosing agents (tetracycline, bleomycin, absolute alcohol).

Case report

A 73-year-old man with a history of peripheral arterial disease and previous bilateral common femoral artery vein patch angioplasty presented to the vascular outpatient clinic with left foot critical limb-threatening ischaemia (rest pain without tissue loss). He underwent successful revascularisation with a right to left femoro-profunda crossover graft (6 mm Dacron Graft with a vein cuff at the outflow anastomosis).

Postoperatively, he developed a lymph leak that initially seemed to dry up but then re-presented as a large lymphocele 6 weeks later. This was aspirated on three occasions and samples sent to Microbiology, yielding no growth. The lymphocele recurred and progressively increased in size, producing increasing discomfort and impairment of mobility.

The next line of management was open surgical drainage, performed almost exactly a year after his crossover graft. A thick-walled sac was evident, with dilated lymphatics heading inferiorly. The Dacron crossover graft was visible at the base of the lymphocele. The sac was dissected off the surrounding tissue and excised leaving a small cuff around the graft. Two large lymphatic pedicles lying inferior to the sac were ligated.

Unfortunately, the lymphocele recurred within days of this re-exploration. Given that any further surgical exploration would almost certainly require dissection around the profunda femoris, possibly compromising his revascularisation, a less invasive option was explored.

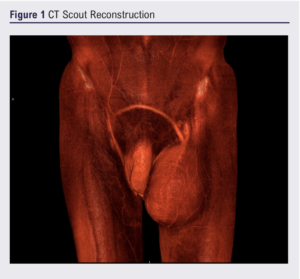

Computed tomography showed a large superficial homogenous hypo-attenuating collection lying anterior to the crossover graft in the left groin. Figure 1 shows a reconstruction of the scout image of that scan.

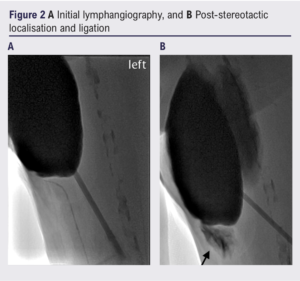

The case was discussed with the interventional radiologists at the multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting. Based on the meeting outcome, we proceeded to a further lymphangiography (via incision over the first web space on the left foot) with a view to identifying an afferent vessel. None was found on the initial scan but a subsequent scan with a larger dose of technetium-labelled nano-colloid showed filling of the lymphocele from a lymphatic vessel adjacent to the course of the left long saphenous vein (Figure 2A).

Given this likely target, he underwent a second surgical procedure (at 17 months post-revascularisation) to ligate the proximal long saphenous vein and peri-venous tissue incorporating the feeding lymphatics.

On review a month later, the swelling had recurred, though less tense. After further discussion at the Vascular MDT, sclerotherapy was chosen as the next step. The lymphocele was aspirated (1500 mL) under ultrasound guidance and the cavity infiltrated with 60,000 units of bleomycin. The drug was left in for 2 hours and removed via a 12F locking Pigtail drain. No untoward local or systemic effects were noted. At that time, it was appreciated that more than one sclerotherapy session was likely to be needed.

However, when the fluid re-accumulated in less than a week, it was decided to switch to 100% ethyl alcohol as the sclerosing agent. A 9F sheath was inserted and a variety of catheters used to try to identify possible feeding vessels but none were found. 100 mL of the alcohol was administered via a 12F drain and left inside the cavity for 6 hours. The drain was left uncapped in situ to assess for recurrence.

A few weeks later the patient reported a recurrence of the swelling, but this time much smaller, with thickening of the overlying skin and subcutaneous tissue. A third sclerotherapy session was then undertaken. This time, only 100 mL of mixed saline and contrast was required to fill the lymphocele. A feeding lymphatic channel was evident in the medial aspect of the thigh and, under 22 gauge stereotactic localisation, was successfully ligated (see patch of contrast marked by arrow on Figure 2B representing its disruption). Another 100 mL of 100% ethyl alcohol was administered into the lymphocele, left in overnight, and aspirated the following morning.

Following the third intervention, the patient reported complete resolution of the lymphocele, with the only symptoms being related to skin induration and occasional discharge from the drain site becoming less and less frequent until complete resolution after 3 months.

On last clinic review, mild lymphoedema was evident in the lower leg but was being managed effectively with compression hosiery. Significantly, he has no symptoms or signs of local or graft-related sepsis or any compromise of his successful revascularisation.

Discussion

Lymphoceles are abnormal lymphatic fluid collections without epithelial lining that form as a result of disruption of lymphatic channels during surgical procedures. The fluid is typically straw-coloured with creatinine concentration closely approximating serum levels.

Lymphoceles most commonly occur after surgical interventions that involve limb and groin areas, pelvic lymphadenectomy or renal transplantation. Increased lymphatic pressure, inflammation, infection, foreign material or scar tissue associated with prior groin exposure all increase the likelihood of persistent lymphocele. They can cause considerable morbidity with significant swelling, pain, sepsis and failure of revascularisation.

The oblique groin incision is thought to be less traumatic to the lymphatic channels and can be a preventative strategy in high-risk patients.1,2 Another way to reduce the incidence is meticulously ligating crossing lymphatic channels in the field of dissection.

Several treatment techniques have been reported. These include repeated percutaneous drainage, marsupialisation, percutaneous image-guided lymphatic ligation (PILL procedure) and sclerotherapy. Percutaneous drainage is usually the first line of treatment for symptomatic lymphoceles. However, the recurrence rate is as high as 60% and the risk of infection increases with every treatment. The PILL procedure, while considered percutaneous, requires a small incision with insertion of a clip applier to occlude leaking lymphatic channels under fluoroscopic guidance using lymphangiography.3 Sclerotherapy is an effective treatment strategy for resistant large lymphoceles. The type of sclerosing agent that is used seems mostly based on the institutional or treating physicians’ preferences. Few data exist on the available treatments and consensus is therefore lacking on the best type, dosage and length of administration of sclerosing agent. Hence, there are no established guidelines or protocols for the use of sclerosing agents.

Bleomycin is a cytotoxic agent. Topical use allows the formation of adhesions, making it an excellent agent for sclerosis. There are some accumulated experiences using bleomycin for sclerosis of malignant pleural effusions and treatment of lymphangioma.4 Common side effects are pain (23%) and fever (19%).

Ethanol and povidone-iodine are frequently used because these are affordable and easily available agents that are generally well tolerated (discounting people with a history of a reaction to povidone-iodine). Ethanol is also minimally painful, especially if 10 mL of 1% lidocaine is added to it. Some surgeons advocate turning the patient into multiple positions to ensure distribution of the alcohol. Up to 100 mL of 100% ethyl alcohol can be injected per sclerotherapy session and 2–3 sessions are usually required. Possible treatment complications include infection, failure to resolve the seroma and injury to adjacent structures by unintended puncture. Intoxication is also possible with use of ethanol.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics like tetracycline, doxycycline and minocycline induce formation of adhesion and fibrosis after intracavitary injection. The therapeutic effect of tetracycline has also been attributed to the fact that it is associated with inhibition of gelatinase activity which could result in decreased collagen breakdown and hence an increased collagen formation.5

Conclusion

Management of a postoperative lymphocele can be complex, more so in the context of a delicate vascular reconstruction as in this case. This was a very challenging situation where a multidisciplinary approach proved beneficial. There are no established guidelines regarding the use of sclerosing agents in these situations. It is very common for large collections to require multiple treatment sessions to achieve a meaningful result.

Article DOI:

Journal Reference:

J.Vasc.Soc.G.B.Irel. 2023;2(2):118-120

Publication date:

February 27, 2023

Author Affiliations:

1. Department of Vascular Surgery, Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, Glasgow, UK

2. Department of Interventional Radiology, Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, Glasgow, UK

Corresponding author:

Manoj D Nair

Department of Vascular Surgery, Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, 1345 Govan Road, Glasgow G51 4TF, UK

Email: [email protected]