EDITORIALS

Blue toe syndrome

Ninkovic-Hall GA,1 Sritharan K2

Introduction

Blue toe syndrome (BTS) is not an uncommon referral, with vascular services often being the first port of call from primary care or the emergency department setting. It is a condition which is often overlooked, misdiagnosed or falsely labelled in the wider medical setting. Nevertheless, it warrants a thorough history, examination and assessment due to its potential implications.

BTS was first named by Karmody et al in 1976,1,2 with the perceived pathophysiology being that of a vascular aetiology. As its name suggests, the basis of its presentation is the finding of blue or purple discolouration of one or more toes, in one or both feet, without a clearly recognised underlying factor.3,4 It typically occurs in the absence of any oblivious trauma, cold-induced lesion or disorders that induce generalised cyanosis.4

Definition and theories

In simple terms, BTS is acute or subacute tissue ischaemia, due to the occlusion of the distal small vessels of the feet and toes, leading to the cyanotic blue appearance of the lower limb digits. In the formative years of its definition, its description included the “3 Ps” – sudden onset Pain, Purple discolouration (of toes or digits) and presence of Palpable peripheral pulses.5

BTS remains a condition which is characterised by the sudden onset of painful discoloured toes and often poses a diagnostic challenge for healthcare professionals. The discolouration ranges from subtle blue hues to dark purple as a result of the compromised blood flow to the extremities.

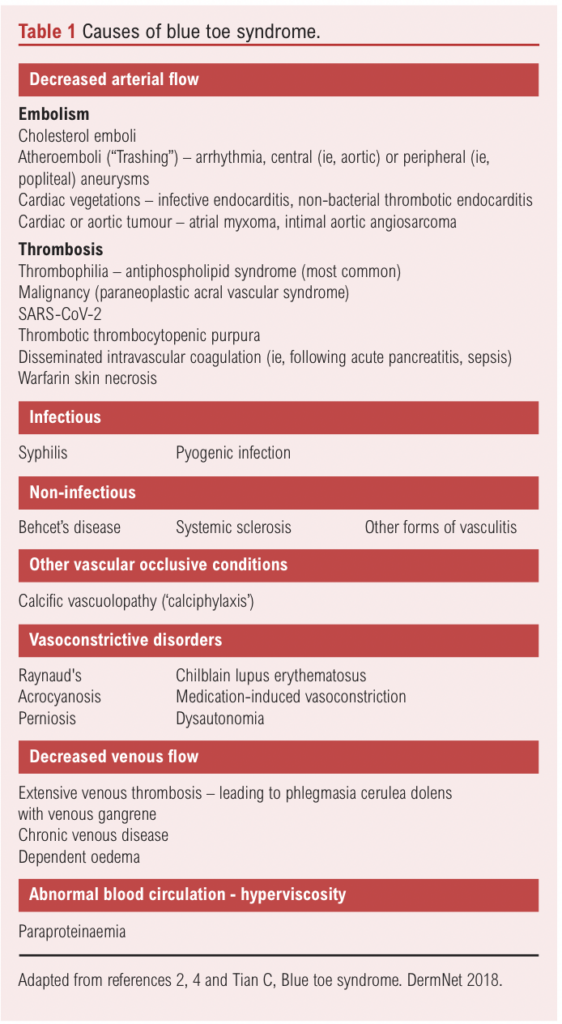

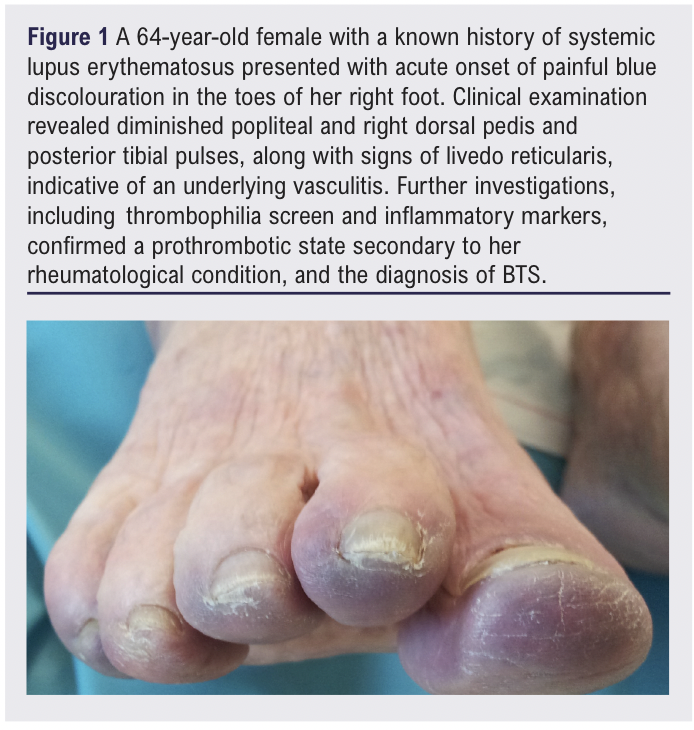

BTS is by nature a very distal vessel occlusive vasculopathy which can be categorised into three broad categories of pathology: decreased arterial flow, decreased venous flow or abnormal circulating blood (see Table 1).4 The initial perceived notion was that it was due to a non-obstructive underlying arterial lesion, with subsequent embolisation from the lesion expaining the frequent presence of palpable peripheral arterial pulses despite the presence of digital ischaemia.2,5 Whilst the condition is frequently associated with underlying atherosclerosis and can serve as a harbinger of systemic vascular diseases such as peripheral artery disease (PAD) or aneurysmal disease,6 cyanosis of the digits may have several aetiologies ranging from trauma to connective tissue disease, but more commonly it is secondary to cholesterol crystal or atherothrombotic embolisation. Importantly, BTS is often an isolated finding and the sole clinical symptom manifestation of an underlying pathology. An extensive differential diagnosis should therefore be considered in a patient who has one or several blue toes with progressive and/or bilateral symptoms, and performing appropriate imaging tests early in patients with BTS is imperative in establishing a diagnosis.7 An example is shown in Figure 1.

Clinical assessment

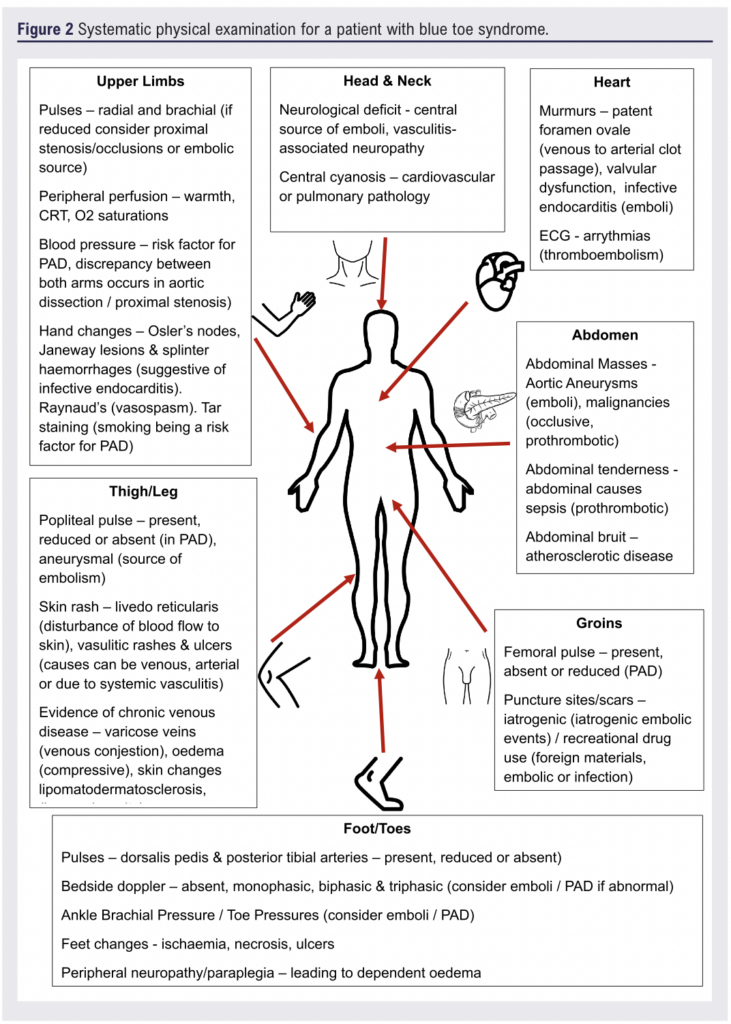

Following a thorough medical, social and family history-taking, an important factor often brushed over is the clinical assessment which is often limited to the lower limb. A more comprehensive multi-system examination can yield important clues to the underlying cause of BTS. Figure 2 highlights the importance of a thorough clinical examination at the time of first review in establishing a cause.

Investigation and diagnosis challenges

Blood tests

The initial investigation should include routine blood tests: full blood count is essential to detect anaemia, infection, inflammation and other haematological conditions that may, for example, affect blood viscosity (eg, polycythaemia); urea and electrolytes are important since vasculitides, lupus and renovascular disease can all impact on renal function; liver function tests can indicate blood clotting and metabolic abnormalities; a coagulation profile is useful to exclude abnormal clotting, which can contribute to embolic or thrombotic events; C-reactive protein is helpful to evaluate and monitor in acute or chronic inflammatory conditions and serum cholesterol levels are a risk factor for atherosclerosis, which is commonly associated with BTS.

If unwell, lactate levels may also be conducted to assess possible metabolic derangement in need of prompt management. Specialised tests in the form of erythrocyte sedimentation rate, thrombophilia and viral screens are typically not first line at the time of vascular assessment but may need to be considered.

Imaging

The largest investigative case series on BTS to date identified aneurysms and short-length severe stenotic arterial lesions as the culprit lesions in the majority of cases.7 In addition, it also reported on the benefit of doppler ultrasound assessment of the arteries in the affected limb, including the aorta and iliac arteries, in establishing a diagnosis; this is therefore recommended as the first-line diagnostic examination.7 Computed tomographic angiography of the aorta and lower limbs and, in some instances, catheter angiography may also be useful in determining a cause.

Beyond the conventional diagnostic methods used to assess arterial vessels, ensuring that there are no central embolic causes for the presentation is imperative, typically with CT aortography of the chest (looking for more proximal aneurysmal or atherosclerotic disease), echocardiogram (for cardio-embolic causes) and 24-ECG Holter (to exclude cardiac arrythmia), is recommended. These tools, when integrated into the diagnostic algorithm, contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the disease, aiding a timely and accurate diagnosis.

It should be noted that one of the primary obstacles in managing BTS lies in its varied aetiology and clinical presentation,4,6,8 and distinguishing between an embolic source, thrombotic occlusion and other potential causes requires a meticulous approach.

Table 1 highlights the primary vascular and secondary vascular causes. Discussion with the relevant specialties should be instigated to allow for a multidisciplinary team approach to patient care.

Management and implications

The management of BTS will be driven by the underlying pathophysiological cause and often demands a multidisciplinary approach. The goals of treatment are to alleviate symptoms, prevent further embolic events, and address the underlying vascular (or non-vascular) cause.

Prompt initiation of anticoagulant therapy is advocated in cases where thromboembolic events are suspected or have been confirmed. This may be in the form of therapeutic Low Molecular Weight Heparin, unfractionated intravenous heparin or a licensed oral anticoagulant. The duration and type of anticoagulation will be determined by the underlying cause.

Where an atheroembolic cause (cholesterol crystal emboli) is suspected, initiation of antiplatelet agents (clopidogrel or aspirin) with high-dose statin therapy is the typical course of treatment. Where events have occurred on a single antiplatelet, addition of a second may be considered. Secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease is vital with hypertension management, smoking cessation and glycaemic control of diabetics, in order to mitigate the risk of further thromboembolic events and enhance peripheral perfusion, particularly in those with likely advanced atherosclerotic disease.9,10

In cases where there is an identifiable source of emboli, whether cardiac or arterial, targeted interventions such as endovascular procedures or surgical revascularisation1,6,8,11 may be warranted, although rare. The decision-making process requires careful consideration taking into consideration the patient’s overall health, comorbidities and the extent of vascular involvement. However, when no obvious underlying vascular pathology or other named cause is found, antiplatelet therapy with monitoring could reasonably be offered.

Pain with BTS can be considerable and unrelenting, necessitating a systematic approach in accordance with the WHO pain ladder.12,13 Initial pain assessment should involve evaluating the severity using a standard pain scale and identifying exacerbating and relieving factors. For mild to moderate pain, the recommended approach includes paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, if not contraindicated. In cases of severe pain, opioids such as morphine or oxycodone may be required with close monitoring, and adjuvant therapies like gabapentinoids can be considered for neuropathic pain.14

Systemic non-cardioselective vasodilators can improve blood flow and alleviate ischaemic pain including calcium channel blockers (eg, nifedipine) and are particularly useful for patients experiencing significant vasospasm.15 Topical vasodilators (eg, glyceryltrinitrate ointment) can be applied to the affected areas to enhance local blood flow and reduce pain while minimising the systemic side effects associated with oral vasodilators.15

Additionally, iloprost, a prostacyclin analogue, can be administered intravenously to manage severe ischaemic pain, ulceration16,17 and BTS.18 Iloprost infusion significantly improves symptoms by enhancing microcirculation and reducing thrombotic events, particularly in cases of cholesterol emboli.19 In instances where pain cannot be controlled, local anaesthetic blocks may be considered.20

Depending on the severity of the ischaemia, time to presentation and response to management, the toes may become non-viable. In these cases, surgical amputation should be considered.

The evolving landscape

The current literature on BTS is limited to case reports and case series. The mainstay of our understanding of the condition comes from clinical expertise passed on from generation to generation of vascular surgeon, with little changing in the overall body of literature and our understanding of BTS from 1975, when the condition was first recognised, to after 1985.

Conclusions

BTS is a complex vascular condition that requires a comprehensive and methodical approach, precise diagnosis and timely intervention. This article hopes not to offer an exhaustive list of possible underlying causes, but to offer a ‘starting block’ for assessing such patients when they present to vascular teams.

Article DOI:

Journal Reference:

J.Vasc.Soc.G.B.Irel. 2024;3(4):190-193

Publication date:

August 27, 2024

Author Affiliations:

1. Specialist Registrar in Vascular Surgery, Countess of Chester Hospital, Health Education England North West, Chester, UK

2. Honorary Senior Lecturer in the Section of Vascular Surgery, Department of Surgery & Cancer, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, London, UK

Corresponding author:

George Ninkovic-Hall

Countess of Chester Hospital, Liverpool Road, Chester,

CH2 1UL, UK

Email: [email protected]