ORIGINAL RESEARCH

The Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland and Rouleaux Club membership survey on the role of Physician Associates in vascular surgery

Hitchman L,1 Long J,2 Egun A,3 McDonnell CO,4 Garnham A,5 Chetter IC1,2

Plain English Summary

Why we undertook the work: Increasing the number of people who work for the NHS is part of the UK government’s NHS Long Term Plan. One way of doing this is to employ Physician Associates (PAs). PAs were introduced in 2003 and are trained to support the multidisciplinary team, under supervision. Recently there has been a big increase in the number of PAs in the NHS. This has caused some vascular surgeons to raise concerns about PAs in vascular surgery departments.

The purpose of this survey was to understand the role PAs currently have in providing care to people with vascular diseases. The survey also wanted to gather vascular surgeons’ opinions on how PAs should be involved in providing care to people with vascular diseases.

What we did: A group of vascular surgeons developed and tested the survey, which contained a mix of multiple choice and free text questions. The survey had four parts which asked questions about:

Part 1: The tasks PAs are currently undertaking in vascular departments

Part 2: How PAs are supervised and trained in vascular departments

Part 3: Vascular surgeons’ opinion on PAs and patient care in vascular surgery

Part 4: Vascular surgeons’ opinion on PAs and doctor workloads and opportunities to train in vascular surgery.

We used an online survey tool to send out the survey to vascular surgeons and trainees in the UK and Ireland in June 2024.

What we found: 194 vascular surgeons from 59 NHS Trusts in the UK and two vascular units in the Republic of Ireland completed the survey. 52 out of 194 (27.8%) vascular surgeons worked with PAs in their vascular department. 60 out of 194 (30.9%) vascular surgeons support the introduction of PAs in the NHS workforce.

The most frequent tasks carried out by PAs included taking a patient’s medical history, examining patients and requesting scans (for example ultrasounds).

Vascular surgeons felt that PAs should not be involved in:

• Performing operations:

– 43 out of 52 (82.7%) vascular surgeons who work with PAs

– 114 out of 142 (80.3%) vascular surgeons who do not work with PAs

• Prescribing medications:

– 33 out of 52 (63.5%) vascular surgeons who work with PAs

– 70 out of 142 (49.3%) vascular surgeons who do not work with PAs

• Training doctors and medical students

– 31 out of 52 (59.6%) vascular surgeons who work with PAs

– 95 out of 142 (66.9%) vascular surgeons who do not work with PAs

Vascular surgeons who completed the survey felt that PAs could have a positive impact on patient care, but the way PAs have been introduced in the NHS has resulted in problems with patient safety, reduced the opportunity for postgraduate doctor training and increased doctors’ workloads.

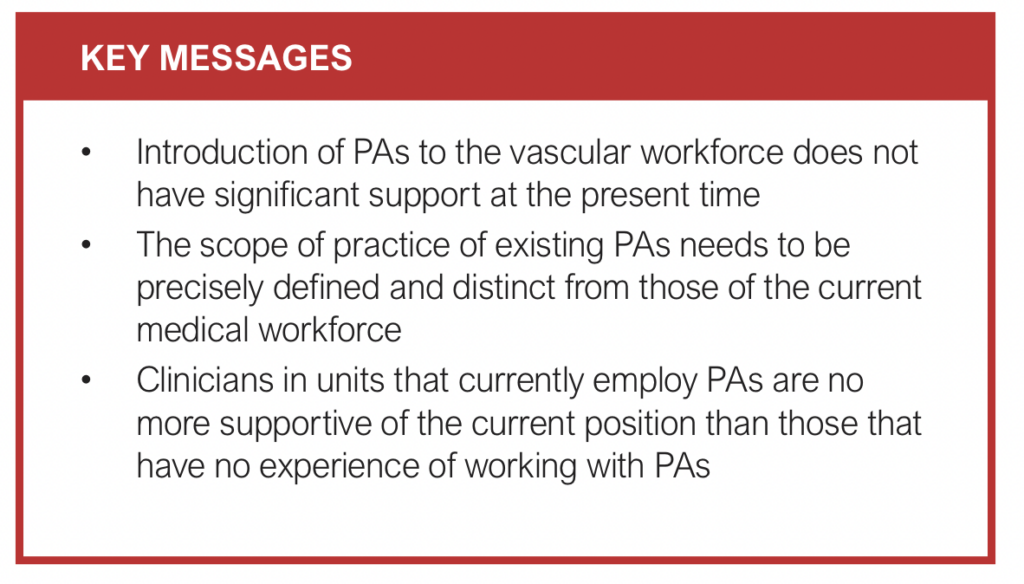

What this means: Currently, the majority of vascular surgeons who completed this survey do not support the introduction of PAs in vascular surgery departments. Vascular surgeons’ concerns about patient safety, appropriate tasks for PAs and postgraduate doctors’ training need to be addressed before more PAs are employed by vascular surgery departments.

Abstract

Background: The UK government’s proposed expansion of the role of Physician Associates (PAs) in the NHS is an ongoing topic of debate. This survey aimed to capture the opinion of members of the Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland (VSGBI) and The Rouleaux Club on the role of PAs in vascular surgery.

Methods: A Qualtrics online survey tool was used to distribute a pre-piloted survey through relevant mailing lists to vascular surgeon members of the VSGBI and the Rouleaux Club. Data were captured on the current role of PAs in vascular surgery and the perceived impact of PAs on patient care, workload and training opportunities. The survey collected responses between 7th and 25th June, 2024.

Results: The survey received 194 responses from 59 NHS Trusts in the UK and two vascular units in the Republic of Ireland. Most respondents were consultant vascular surgeons (98/194; 51%). Of the respondents 26.8% (52/194) worked with PAs. 69.1% (134/194) of respondents do not support the presence or introduction of PAs in vascular surgery. The most frequent tasks carried out by PAs included taking a medical history (42/52; 86.5%), physical examinations (40/52; 76.9%) and requesting diagnostic investigations (excluding ionising radiation) (37/52; 71.2%). Respondents felt that PAs should not be involved in performing procedures (units with PAs: 43/52, 82.7%; units without PAs: 114/142, 80.3%), prescribing (units with PAs: 33/52, 63.5%; units without PAs: 70/142, 49.3%), training resident doctors/medical students (units with PAs: 31/52, 59.6%; units without PAs: 95/142, 66.9%). Themes that arose from the free text responses included the potential positives of PAs, organisation flaws that have led to the perceived problematic introduction of PAs and the negative impact of PAs on patient safety, resident doctor training and doctors’ workload.

Conclusions: Fewer than a third of the vascular surgeons who responded to this survey were supportive of the introduction of PAs into vascular surgery. This is driven by concerns for patient safety, unclear scope of practice and perceived negative impact on medical training.

Background

Physicians Associates (PAs) were first introduced in the UK in 2003. They work under the supervision of doctors and undertake day-to-day tasks in general practice and hospital settings. They undertake a two-year postgraduate degree which focuses on the general aspects of adult medical care.1 PAs are not part of the medical or nursing staff and are classified as medical associate professionals.2 They are paid on the agenda for change pay system, with a band 6 starting salary (£37,338 to £44,962) which can rise to band 8 salary (£53,755 to £101,677) depending on experience.1,3 The majority of PAs are women and under 30 years of age.4 There is no defined career pathway for PAs: they often move between specialities, especially in their first few years of entering the workforce.4

Several initiatives introduced by the UK government indicate a commitment to expanding the number and role of PAs. The NHS Long Term Plan and the NHS People Plan (2020) both support the expansion of PAs, highlighting the potential to address workforce shortages and enhance patient care.5,6 In December 2023, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) produced a consultation process that gave the General Medical Council (GMC) a framework for regulation of PAs.7

However, the planned expansion of PAs in the NHS has proven to be a highly contentious and ongoing topic of debate. It has prompted several professional societies to release statements opposing the initiative. Frequently cited concerns relate to patient safety, questionable standards, scope of practice and negative impact on medical trainees.8 The British Medical Association (BMA) went as far as to call for an immediate halt to PA recruitment,9 and in June 2024 launched legal action against the GMC over its plans to regulate PAs and anaesthesia associates (AAs).10

The Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland (VSGBI) is engaged with the Surgical Royal Colleges and the Federation of Specialist Surgical Associations (FSSA) to define an appropriate scope of practice for PAs working within vascular services in the UK and Ireland. Before releasing an official position statement, the VSGBI in collaboration with The Rouleaux Club, who represent vascular surgical trainees, sought to gather input from their membership to ensure their position is representative. The aims of this survey were to explore how PAs are currently working in vascular surgery and to understand the opinions of VSGBI and Rouleaux Club members regarding the role of PAs in vascular surgery. These findings, along with further discussions, will help guide the VSGBI and The Rouleaux Club in shaping an informed position on the role of PAs within vascular surgery.

Methods

Survey design

This report adheres to the reporting recommendations from the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES).11 The survey was developed by a sub-group of members from the VSGBI and Rouleaux Club committees, aiming to capture the perspectives of vascular surgeons and trainees on several key areas. Specifically, it sought to: 1) examine the roles and tasks that PAs are currently undertaking within their units, and determine which roles are considered suitable or unsuitable; 2) assess the supervision, training and accountability mechanisms for PAs; 3) collect opinions on PA impact on patient care and safety; and 4) evaluate the impact of PAs on doctor workloads and training opportunities for vascular trainees. Questions in the second section of the survey were adapted from the BMA’s Medical Associate Professionals survey.12

Pilot round one

In April 2024 an initial survey was drafted by a subgroup of the VSGBI committee, consisting of two vascular consultants and a project manager, each with experience in administering national surveys. The survey was generated using Qualtrics online survey tool (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) and was distributed to the VSGBI elected council members for the first round of feedback. Following review, several modifications were made to enhance clarity and comprehensiveness.

The modifications included inclusion of the Royal College of Physicians Faculty of Physician Associates (RCP FPA) definition of a PA to the introduction, to help respondents understand the specific role being addressed. The inclusion of vascular unit identifiers was debated but ultimately retained to assess representation from the responses. Additional options were incorporated to the questions that cover potential procedures undertaken by PAs, in addition to procedures referenced on the FPA website.

To understand the quantitative results of the survey, free text comment boxes were introduced in the later sections, giving respondents the opportunity to provide detailed feedback on their views about PAs. Although it was recognised that the inclusion of free text would significantly lengthen the survey and subsequent analysis, it was considered vital to allow respondents the chance to expand on their answers.

Pilot round two

A second draft was recirculated to the VSGBI council in May 2024 and, following feedback, minor clarifications were made. This included adding options for respondents to indicate whether their units did not currently employ PAs, while still allowing them to share their views where applicable. Demographic questions were also expanded to enhance inclusivity, ensuring that all membership levels – not just consultants – could be identified. This adjustment enables a more detailed analysis, allowing for a comparison of perspectives between consultants and trainees.

The final survey was circulated by email to vascular surgeons and trainees via their societies (see Appendix 1 online at www.jvsgbi.com). The survey was open between 7th and 25th June, 2024 with a reminder email on 14th June, supported by social media promotion throughout. The survey consisted of 30 questions and the response types included a selection of options from a pre-defined list, Likert matrix questions and free text comments. Where the option of ‘other’ was provided, space to give further detail was included. At the end of the survey, respondents were invited to volunteer their contact information if they expressed an interest in being part of a working group on the role of PAs in the vascular specialty.

Data management

Access to data within Qualtrics was restricted to authorised survey administrators, who were Good Clinical Practice (GCP) trained. Data were securely downloaded into a password-protected file and held on NHS computers. Any blank data sessions were excluded from the analysis. Analysis was led by a vascular research fellow at ST3 level (LH) and a project manager at MA level with significant experience of reporting survey results (JL). The process was overseen by the subgroup of the VSGBI council.

Data analysis

Numerical and Likert-scale data from the questionnaire were collated and presented descriptively, with results stratified by respondent type where relevant.

For the qualitative analysis, content analysis was conducted on more than 600 free-text responses. Two authors (LH, JL) independently coded responses. Afterwards, they reconvened to compare codes, utilising research triangulation to combine and refine them. For responses with ambiguous or unclear meanings, discussion and consensus were used to assign appropriate codes. Following this coding process, categories were created through collaborative discussion and reflection. Responses were then assigned to these categories using a consensus approach. After reviewing the categories and subcategories, themes were generated, which were further refined through discussion, with each category ultimately assigned to an overarching theme.

The data were analysed using Qualtrics and Microsoft Excel (2021; WA, USA).

Ethical consideration

The survey was completed voluntarily by vascular surgeons and vascular specialty trainees. The voluntarily completion of the survey was considered consent for participation. No patient data were collected and the results are not presented by unit or respondent, to ensure anonymity.

Results

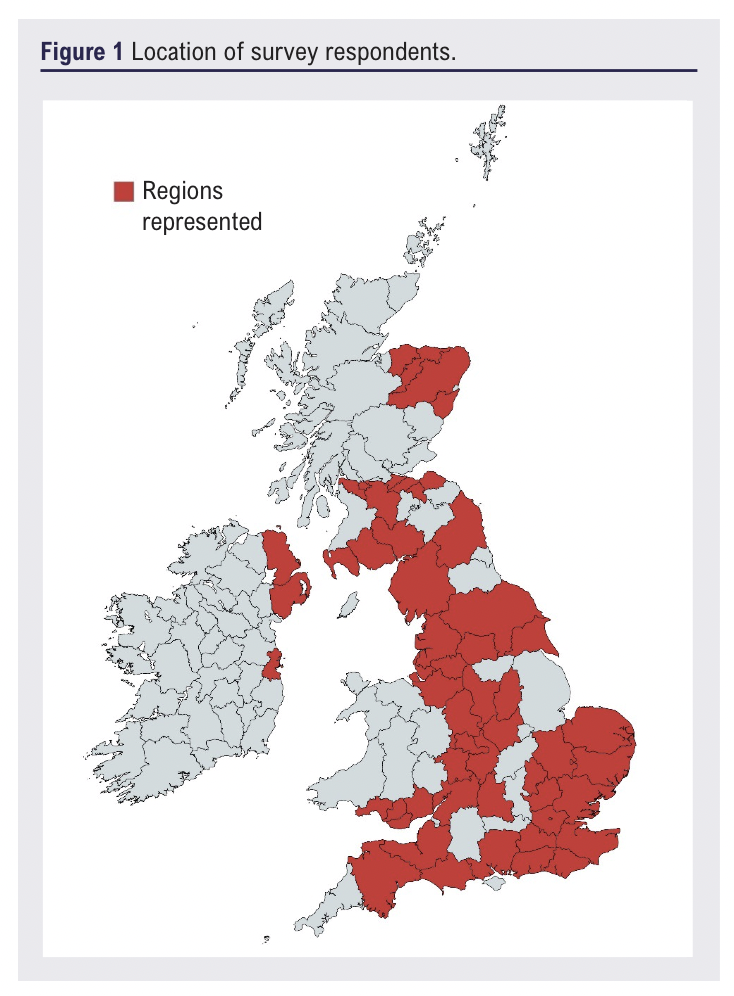

The survey received 194 responses from 59 NHS Trusts in the UK and two vascular units in the Republic of Ireland (Figure 1). Three respondents did not wish to disclose their location, one respondent reported they were retired, one respondent worked overseas and one respondent worked exclusively in private practice. The survey was completed by 98 (51%) vascular surgery consultants, 70 (36%) trainees, 12 (6%) associate specialists, four (2%) senior VSGBI members, one (0.5%) honorary VSASM member, two (1%) overseas vascular surgeons and seven (4%) who identified as ‘other’, but did not specify their job role. 52 (27.5%) respondents reported that PAs were employed by their vascular unit.

Overall, only 30.9% (60/194) of respondents supported the presence or introduction of PAs in vascular surgery. Support was higher from respondents in vascular units who currently employ PAs (29/52, 55.8%) than from those in vascular units without PAs (31/137, 22.6%). In vascular units with PAs, 40.5% (21/52) of respondents were involved in the decision to recruit PAs, 25.0% (13/52) were involved in writing the PA job description and 23.1% (12/52) were involved in interviewing potential candidates. Four (7.7%) respondents reported that their vascular unit had no involvement in the recruitment of PAs. The majority of respondents (132/194; 68%) felt the public did not understand or were unsure about the difference between a PA and a doctor.

1. Scope of practice

In vascular units with PAs tasks frequently performed by PAs included taking a medical history/writing in the medical notes (45/52; 86.5%), carrying out physical examinations (40/52; 76.9%), requesting diagnostic investigations (excluding ionising radiation) (37/52; 71.2%), maintenance of clinical records (34/52; 65.4%), providing health promotion and disease prevention (27/52; 51.9%), and formulating differential diagnoses (23/52; 44.2%). Other tasks include assisting in the operating theatre (19/52; 36.5%), developing patient management plans (19/52; 36.5%), teaching and examining medical students (17/52; 32.7%), interpreting diagnostic studies (17/52; 32.7%), undertaking research (16/52; 30.8%), requesting ionising radiation (16/52; 30.8%), wound closure (including suturing) and wound care (including applying dressings) (14/52; 26.9%), performing procedures while supervised (14/52; 26.9%), training and assessing resident doctors (13/52; 25.0%), prescribing (8/52; 15.4%), giving prescribed medications (7/52; 13.5%), and performing procedures unsupervised (4/52; 7.7%).

Tasks respondents felt that PAs should not undertake include performing procedures without supervision (43/52; 82.7%), performing procedures supervised (35/52; 67.3%), prescribing (33/52; 63.5%), training and assessing resident doctors (31/52; 59.6%), interpreting diagnostic studies (28/52; 53.8%), requesting ionising radiation (28/52; 53.8%), assisting in the operating theatre (27/52; 51.9%), developing patient management plans (27/52; 51.9%), teaching and examining medical students (26/52; 50.0%), and performing wound closure and wound care (25/52; 48.1%).

In vascular units without PAs, respondents reported they would not support PAs performing procedures unsupervised (114/142; 80.3%), training and assessing resident doctors (95/142; 66.9%), teaching and examining medical students (93/142; 65.5%), interpreting diagnostic imaging (93/142; 65.5%), performing procedures under supervision (91/142; 64.1%), developing patient management plans (84/142; 59.2%), requesting diagnostic investigations (including ionising radiation) (80/142; 56.3%), assisting in the operating theatre (71/142; 50.4%), prescribing (70/142; 49.3%), and wound closure and care (70/142; 49.3%). Other tasks respondents would not support PAs undertaking include formulating differential diagnoses (60/142; 42.3%;), administering medication (54/142; 38.0%), requesting diagnostic investigations (excluding ionising radiation) (50/141; 35.2%), carrying out physical examinations (41/142; 28.9%), taking medical histories and writing in patient notes (34/142; 23.9%), research (27/142; 19.0%), providing health promotion and disease prevention advice (22/142; 15.5%), and maintaining clinical records (21/142;

2. Training and governance

Respondents reported that PAs had received specific training to undertake the following tasks in their vascular unit: phlebotomy (34/52; 65.4%), peripheral venous cannulation (31/52; 59.6%), urinary catheterisation (26/52; 50.0%), measuring ankle brachial pressure indices (26/52; 50.0%), assisting in the operating theatre (15/52; 28.8%), performing wound closure and wound care (13/52; 25.0%), radiation protection (5/52; 9.6%), administering medication (5/52; 9.6%), performing endovenous therapy (5/52; 9.6%), and performing ultrasound assessments (5/52; 9.6%).

PAs were most frequently supervised by a named consultant (21/52; 40.4%) or a supervisory consultant group (20/52; 38.5%). Other respondents reported that trainees (8/52; 15.4%) and senior nurses (3/52; 5.8%) also supervised PAs. Respondents reported that PAs were accountable to the supervisory consultant group (17/52; 32.7%), a named consultant (17/52; 32.7%), senior nurses (3/52; 5.8%) and trainees (1/52; 1.9%). Supervision was often not accounted for in consultant surgeons’ job plans, with only 5 (9.6%) respondents reporting the named supervising consultant had time allocated to supervise PAs.

Twenty-three (44.2%) respondents reported that the hospital provided PAs with an annual appraisal. 46.2% (24/52) of respondents reported they did not know whether PAs were appraised annually by the hospital and one (1.9%) respondent reported PAs did not have an annual appraisal at their hospital. Fifteen (28.8%) respondents reported that the hospital provided continued professional development (CPD) for PAs. CPD activities included audits (10/52; 19.2%;), teaching (10/52; 19.2%), conference attendance (10/52; 19.2%), course attendance (9/52; 17.3%), reflective diaries (4/52; 7.7%) and research (4/52; 7.7%).

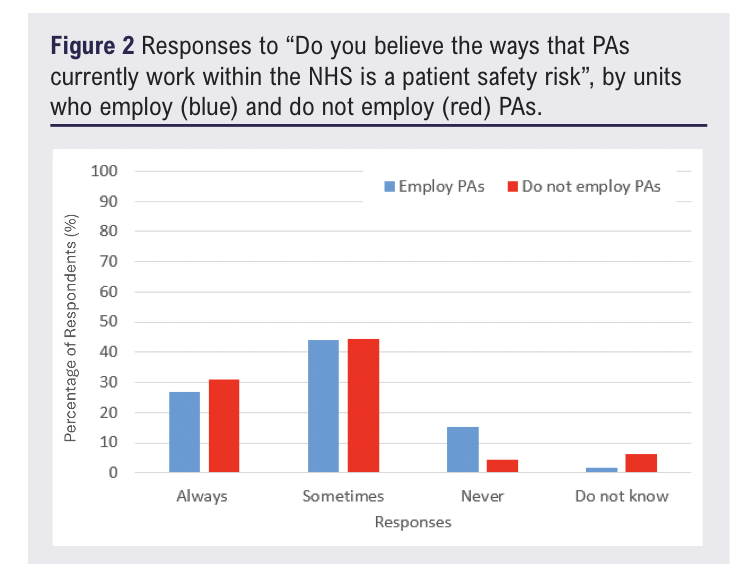

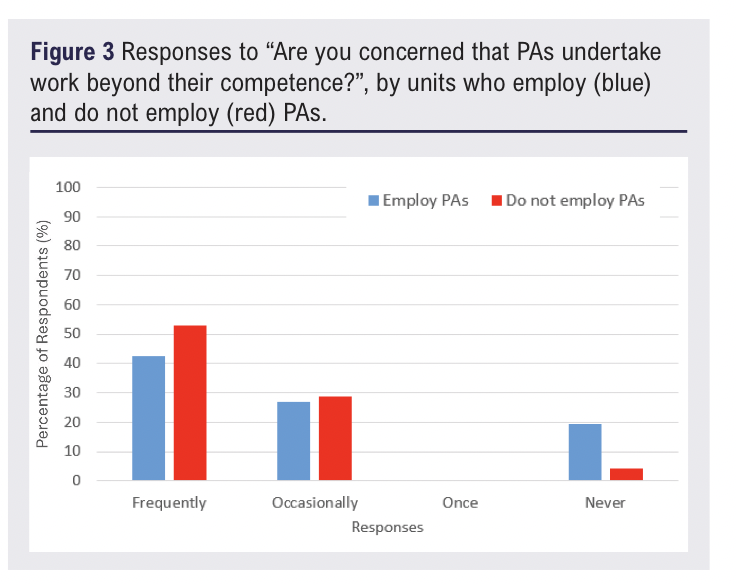

3. Patient care and safety

Improvement in patient care associated with the introduction of PAs was reported by 25/52 (48.1%) respondents who currently work alongside PAs and 9/142 (6.3%) of respondents who don’t. The majority of respondents felt the way PAs currently work within the NHS is a patient safety risk (Figure 2) and that PAs worked beyond their competency (Figure 3). These findings were evident whether or not the respondent was working alongside PAs.

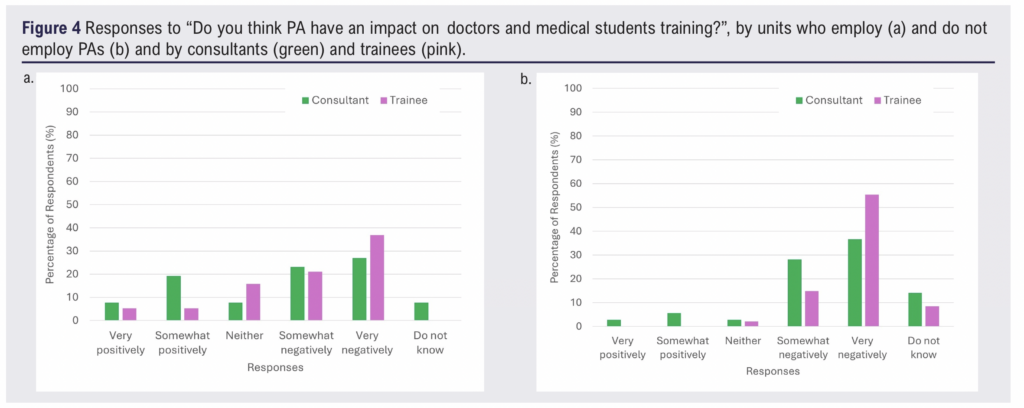

4. Impact on medical training, recruitment & retention and

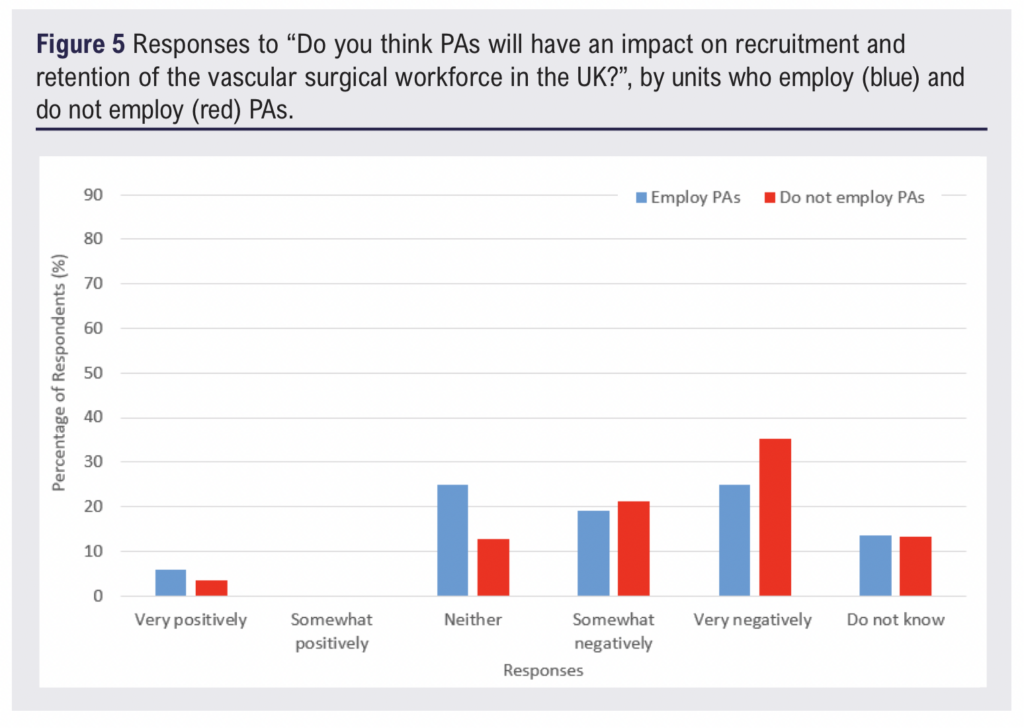

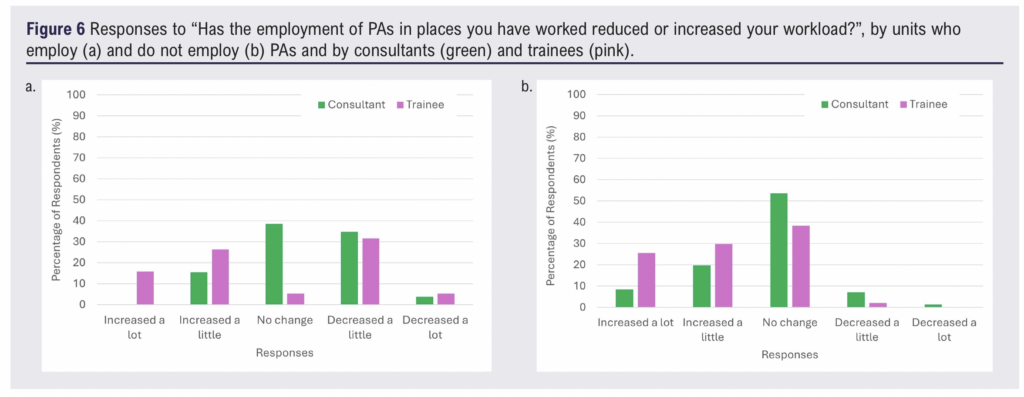

Respondents felt that PAs have negatively impacted resident doctor and medical student training (Figure 4) and have had a negative impact on recruitment and retention to vascular surgery (Figure 5). These findings were evident whether or not the respondent was working alongside PAs. The impact on workload was variable but relatively limited in magnitude (Figure 6).

Qualitative results

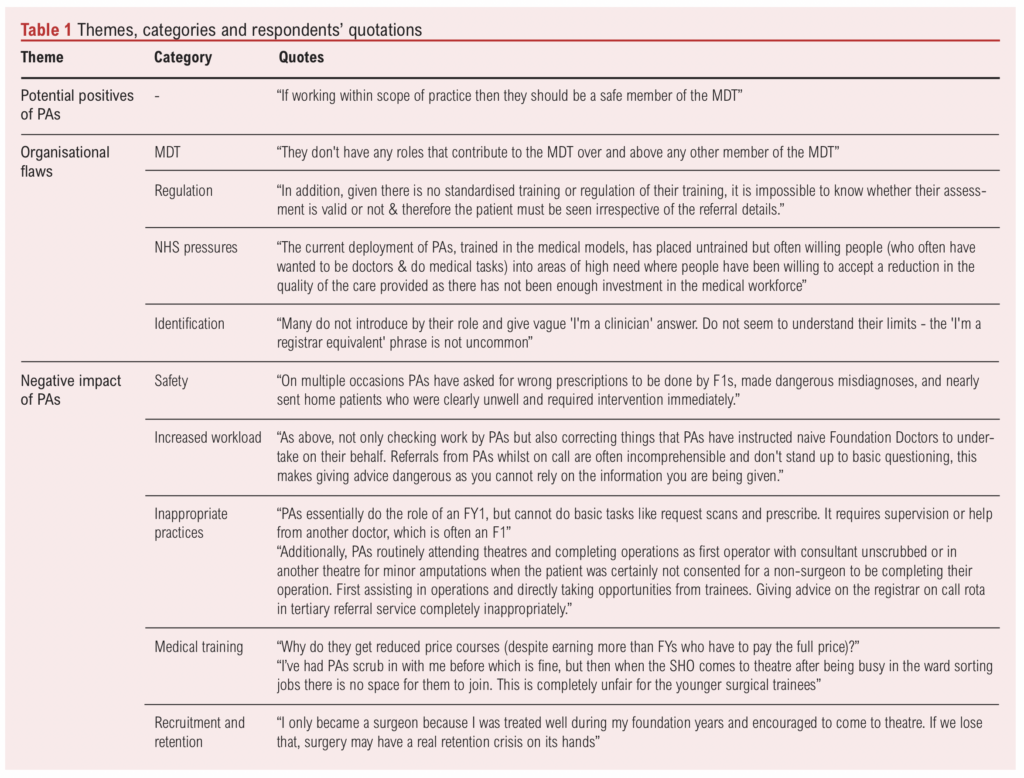

Four hundred and sixty codes were analysed into 10 categories. The 10 categories were formed into three overarching themes (Table 1).

Potential positives of PAs

Respondents felt that PAs could offer a positive impact to the NHS with clear role definition and appropriate supervision. Specific positives included providing continuity of patient care and supporting new staff induction. Respondents felt the permanent nature of PAs (who do not rotate) would aid in administrative tasks, such as ward round documentation and organisation, due to familiarisation with hospital systems and protocols.

The presence of PAs could also alleviate the pressures of service provision for resident doctors if they performed ward-based tasks that do not require a doctor, such as phlebotomy and peripheral venous cannulation. Respondents felt that this would allow resident doctors to attend more training opportunities and therefore improve medical training.

Some respondents felt the introduction of PAs might also increase patients’ access to doctors. Patient triage performed by a PA could help to identify and escalate patients with pathology who require input from a doctor. This could reduce delays in care and help to reduce health inequalities in understaffed regions.

Organisational flaws

Organisational flaws describe problems respondents felt were associated with the introduction of PAs. This encompasses the lack of regulation of PAs, NHS pressures, ambiguous identification of PAs and the unclear role of the PA in the vascular multidisciplinary team (MDT).

Increasing NHS pressures due to staff shortages led respondents to speculate whether the introduction of PAs was to increase the number of staff on the ward without considering quality of care or cost-effectiveness. A particular concern was PAs filling doctor vacancies, especially for international medical graduates, as a cheaper alternative. This was evidenced by the presence of PAs on resident doctor on-call rotas. Respondents felt that the NHS should be investing in doctors and advanced practitioners instead of PAs.

At the time of this survey PAs were not regulated and this was an area of major concern for respondents. The lack of regulation means that PAs currently do not have a nationally defined scope of practice. Respondents interpreted lack of scope as PAs having no role, a limited role or an unclear role in vascular surgery. Without a scope of practice respondents were concerned about ‘scope creep’ and the impact on doctors, especially doctors in training. This relates to some responders feeling that PAs are working beyond their competency. The lack of regulation also led to respondents’ apprehensions about the rigour of the PA qualification. There was a lack of clarity on PA postgraduate training and therefore career pathway. This uncertainty resulted in respondents questioning the role PAs should fill in vascular surgery. To address these concerns respondents felt regulation is necessary to define the scope of PAs and ensure accountability, responsibility, accreditation and ethics of PA practice. This would also address respondents’ concerns about the PA professionalism and curb inappropriate PA behaviour on social media, PAs comparing themselves to training grade doctors, and ensure PAs were aware of their level of competence.

The lack of regulation is related to the confusion in identifying a PA. Respondents reported interactions where PAs appeared to be masquerading as doctors. To healthcare professionals this was by either identifying themselves as an equivalent to a training grade doctor or giving an unclear role e.g. one of the surgical team. To patients this was failing to correct a patient who assumed them to be a doctor. Respondents also felt the use of the word ‘physician’ in the title led to confusion about whether a PA was a doctor or not.

Respondents felt the vascular multidisciplinary team included a wide range of healthcare professionals, appropriately regulated through governing bodies with a well defined scope of practice. PAs were thought to be surplus and to bring no additional benefit to the vascular MDT. There was a feeling that development of the current vascular multidisciplinary healthcare professionals would be a more productive use of resources.

Negative impact of PAs

This theme describes how respondents felt PAs have a negative impact in the NHS. Specific areas include inappropriate PA practices leading to an increased risk of harm to patients and reduced quality of medical training, increase in doctors’ workload and reduction in recruitment and retention to vascular surgery.

Respondents believed some of the tasks performed by PAs are inappropriate as PAs do not have a medical qualification or structured postgraduate training. Specific tasks include assisting and operating in the operating theatre and working on doctor on-call rotas. Respondents reported PAs performed (supervised or unsupervised) major lower limb amputations, vascular interventional radiology procedures and venous procedures. Respondents felt that PAs either assisting or operating was inappropriate. This was due to issues with patient consent, ability to demonstrate competency to undertake the procedure and ability to manage the patient as a whole (e.g. prescribing and decision-making). Inclusion of PAs on vascular registrar rotas was felt to be inappropriate because PAs did not hold the knowledge to be able to assess and manage unselected patient referrals. Potential consequences included PAs giving incorrect medical advice, missed diagnoses and delays in patient care. Respondents reported that inclusion of PAs on vascular registrar rotas also led to some PAs equating themselves to speciality registrar equivalent. Inclusion of PAs on foundation and core level doctor rotas was also felt to be inappropriate as PAs are unable to perform the tasks required (e.g. prescribing medication and requesting ionising radiation investigations). This resulted in PAs prescribing using doctors’ log-in details and pressuring the foundation level doctors to prescribe on their behalf.

Respondents raised concerns about the impact of PAs on surgical training. Some respondents felt consultants had a competing interest when delivering training. Resident doctors felt PAs would receive preferential training as they did not rotate, only work during the day and have more opportunity to build relationships with consultants. The presence of PAs was felt to increase competition for training, especially to attend the operating theatre and clinics. For registrar level doctors this increased competition to access to vascular interventional radiology and venous operative training. For core trainee level doctors PAs reduced their exposure to the vascular operating theatre and clinics. For foundation years PAs were felt to be taking opportunities for them to learn on the ward. Respondents felt PAs reduced their exposure to vascular surgery, with an associated detrimental effect on recruitment. As well as increasing the competition for training, trainees were disgruntled over reduced or fully funded course fees for PAs (e.g. basic surgical skills) and prescribing on behalf of PAs who have a higher salary than they do. Trainees felt consultants viewed trainees’ and PAs’ training requirements to be equivalent.

PAs were felt to increase doctors’ workload. This is because their work needed to be duplicated as respondents did not think PAs were able to assess patients accurately or initiate appropriate management. Poor quality and inappropriate referrals, along with the inability to hold a medical discussion, resulted in increased workloads for doctors when a PA was involved. There were also pressures from PAs to prescribe medications and ionising radiation for patients they had reviewed. This leads to increased doctor workload due to the need to review and request investigations and prescriptions suggested by PAs. As well as duplicating and increasing clinical work, consultants reported that PAs required more supervision than resident doctors. The increased workload could contribute to burnout of doctors. The workload was felt to increase particularly if PAs were on doctors’ rotas.

Respondents felt the widespread introduction of PAs could reduce recruitment and retention to vascular surgery. Reduced exposure due to increased competition for foundation and core level doctors could lead to a decrease in applications to vascular surgery. For vascular surgery trainees increased competition for operative training could lead to trainees feeling disenfranchised and leaving training programmes. Consultants reported they might avoid units that employ PAs, and others reported it would be a reason not to work in the NHS.

Patient safety was thought to be negatively affected by PAs working without a scope, leading to patient harm and inferior quality of care. This could lead to an increase in litigation cases.

Discussion

The survey found the minority of respondents were supportive of the inclusion and introduction of PAs into vascular services. Reasons for this included the poorly defined role of PAs in vascular surgery, the lack of PA regulation, perceived negative impact on patient safety and concerns about medical training capacity.

Professional societies and Royal Colleges have struggled to define the gap in the allied medical workforce that the introduction of physician associate addresses. Surveys conducted by the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) and the Association of Surgeons in Training (ASiT) reported that currently PAs have a very limited role but they could be useful in supporting efficient ward work and delivering advice on lifestyle modification to patients.8,13 Respondents to this survey shared a similar view, acknowledging the wide range of existing disciplines within the vascular profession who deliver the breadth of care required. Support and development of existing roles within the vascular MDT were considered to be more efficient rather than trying to find a role for PAs.

One of the major issues raised in this survey was the lack of regulation of PAs and therefore the lack of accountability, professional standards and nationally recognised continued professional development. Currently the GMC are posed to regulate PAs. This has been met with legal challenges, supported by the BMA, who believe a joint regulator is inappropriate as this would further the misunderstanding held by the public on the difference between a PA and a medical doctor.8,14 The lack of regulation, and therefore postgraduate training and accountability, has recently been raised in the UK courts by a Coroner’s report. The Coroner advised that future deaths could be prevented by the registration and regulation of PAs, and introduction of a national framework on how PAs are trained, supervised and deemed competent. The report also advised cautious use of the word ‘physician’ in PAs’ titles.15

Patient safety concerns raised by respondents in this survey echo results of other surveys and Coroner reports.8,13,15,16 This was driven by their performing procedures without adequate supervision or competency, making inappropriate clinical decisions and lack of appropriate supervision.8,17 Respondents in this survey felt that PAs undertaking procedures, supervised or unsupervised, was an unacceptable practice. Respondents in this survey reported PAs are able to perform more procedural skills compared to a report published by the RCP FPA in 2019.18 This could reflect that this survey was undertaken in vascular surgery and the evolving role of PAs over time.

Respondents also felt the impact of PAs could negatively influence the medical workforce. The VSGBI acknowledge the shortage of consultant vascular surgeons and the need to train significantly more vascular surgeons to maintain a safe 24 hours, 7 days a week service to meet the demands of the growing and ageing population.19 Along with results from this survey, ASiT identified that the presence of PAs negatively impacts foundation and core level trainee doctors disproportionately, which could deter them from applying to the speciality.8 For higher surgical vascular trainees there is a pressure to meet certification requirements, especially with regards to competency in performing open aortic aneurysm repairs and varicose veins procedures.20 Diverting training opportunities to a group who will not address the challenges of a decreasing consultant workforce was a major concern for respondents. The potential negative impact on medical training was also a contributing factor to the RCP’s and Royal College of Anaesthetists’ stance on halting the expansion of PAs.21

To address the concerns raised by professional medical bodies and other stakeholders the UK government have commissioned a report on the independent review on PAs and AAs, led by Professor Gillian Leng. The review aims to consider the scope of PAs, the role of PAs, the support PAs offer the wider health teams, their role in providing good quality and efficient care, and the future of this role in the NHS, to inform the future debate on this topic.22

This survey has limitations. The survey was open for a short period of time, which could have resulted in selection bias. However, the survey received a good response rate, wide geographical spread in England and data saturation was reached in the qualitative responses. The survey aimed to structure questions in a non-leading way and provided a definition of the role of a PA at the beginning of the questionnaire. This aimed to reduce response bias.

Conclusion

This survey reports that patient safety concerns, governance issues, negative impact on medical training, potential impact on recruitment and retention associated with the introduction of PAs currently outweighs any potential benefits. These concerns persist in respondents with experience of working alongside PAs and therefore cannot be accounted for by lack of experience or exposure to working with PAs. The VSGBI and Rouleaux Club therefore cannot support the expansion of PA numbers and scope within vascular surgery. We would urge politicians and health service leaders to find alternative solutions to workforce problems whilst working with specialist organisations and Royal Colleges to define roles for colleagues within the current services.

Article DOI:

Journal Reference:

J.Vasc.Soc.G.B.Irel. 2025;4(2):64-73

Publication date:

February 28, 2025

Author Affiliations:

1. Hull York Medical School, UK

2. Hull University Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, UK

3. Lancaster Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, UK

4. Mater Misericordiae University Hospital, Dublin

5. The Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust

Corresponding author:

Louise Hitchman

Academic Vascular Surgery Unit, Allam Diabetes Centre, Hull Royal Infirmary, Anlaby Road, Hull, HU3 2JZ, UK

Email: [email protected]