ORIGINAL RESEARCH

A feasibility survey to inform trial design investigating surgical site infection prevention in vascular surgery

Lathan R,1* Hitchman L,1* Long J,1 Gwilym B,2 Wall M,3 Juszczak M,3 Smith G,1 Popplewell M,3 Bosanquet DC,2 Hinchliffe R,4 Pinkney T,3 Chetter I1

Plain English Summary

Why we undertook the work: Wound infections affect up to 4 in 10 people who undergo an operation involving a cut in the groin or a leg amputation. Wound infections are painful, debilitating and cause depression and anxiety. They also increase the risk of being admitted to hospital and having another operation. There is sparse good quality research on the best treatment to prevent wound infections after an operation, which are called surgical site infections (SSI). This means different surgeons do different things, which results in variation of care. We are designing a study to compare different treatments to prevent SSI. The first step was to find out which treatments surgeons currently use and whether they would be willing to use an alternative treatment. This will help us to decide which treatments to research in the study.

What we did: We created an online questionnaire asking vascular surgeons which treatments they currently use to prevent SSI when performing an amputation or operating on the groin. The questionnaire also asked whether they would be willing to use different treatments in a study setting. Before we sent out the questionnaire we tested whether it asked the right questions and collected appropriate answers. We tested the questionnaire by sending it to a group of vascular surgeons who suggested changes. We repeated this process until no further changes were needed. The questionnaire was sent out on 10 August 2023 and surgeons had until 30 September 2023 to complete the questionnaire. We sent the questionnaire out via a newsletter from the Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland and tweeted the survey on X (formally Twitter).

What we found: The questionnaire was completed by 58 vascular surgeons in the UK and Ireland. Before the operation surgeons often did not recommend a specific cleanser for bathing. Surgeons used a range of sterilising solutions to clean the skin before they made the first incision. Sometimes films are used to cover the skin, which can be plain or contain iodine. The questionnaire found no agreement between surgeons on the type of film used or using a film at all. Whether antibiotics were given and the course of antibiotics also varied. During the operation surgeons used different solutions to wash the wound or did not wash the wound. A drain was variably used. Most surgeons did not change their gloves or instruments before suturing the skin. The method and type of suture to close the wound also varied. There was no consensus on which type of dressing to use to cover the wound. Nearly 75% of surgeons who completed the questionnaire would be willing to use a different treatment to prevent SSI and would be agreeable to randomise (randomly allocate) to a different treatment in a study.

What this means: This questionnaire found that surgeons use many different treatments to prevent SSI in the UK. We found most surgeons would be willing to try out different treatments in a study. The results will be used to decide which treatments to test in a future study.

Abstract

Introduction: Current surgical site infection (SSI) prevention guidance indicates low-quality evidence supporting many of their recommendations. Subsequently, there is substantial variation in practice and often implementation of unsubstantiated interventions. There is therefore a need to rapidly evaluate best practices to prevent SSI. This survey aimed to evaluate current practice in the prevention of SSI and equipoise regarding potential interventions to reduce SSI rates in major lower limb amputation (MLLA) and groin incisions.

Methods: A cross-sectional national survey was developed from current international guidelines to prevent SSI, following CHERRIES and CROSS checklists. A study steering committee directed internal validation prior to dissemination via single stage sampling of the membership of the Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland.

Results: The survey received 58 responses from clinicians across 38 NHS trusts. Most respondents were consultant vascular surgeons (91%; 53/58). Preoperatively, there was variable practice in the use of preoperative bathing, surgical site preparation, antibiotic prophylaxis duration and the use of incise drapes for both MLLA and groin incisions. Intraoperatively there was little consensus for wound irrigation, drain insertion, changing gloves and instruments prior to skin closure, skin closure technique, and the use of dressings for both MLLA and groin incisions. The majority of respondents were willing to randomise patients to most interventions. Nearly three-quarters (72%; 42/58) of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that a combined outcome measure of SSI and wound dehiscence would be the ideal primary outcome in a trial investigating SSI prevention in MLLA.

Conclusions: Despite significant heterogeneity in practice to prevent SSI, the majority of surgeons surveyed showed they would be willing to randomise to interventions in a randomised controlled trial. This key finding is important in the design of future studies.

Introduction

Surgical site infection (SSI) is common following vascular surgery, complicating up to 40% of groin incisions and major lower limb amputations (MLLA).1–3 SSI significantly impairs quality of life due to associated pain, reduced mobility, depression and anxiety.4 SSI results in a fourfold increase in the risk of readmission and substantially increases healthcare costs, estimated at £6,103 per episode.5,6

The need for a high-quality, appropriately powered, multicentre, randomised controlled trial to inform SSI prevention practice is paramount. National and international SSI prevention guidelines highlight a clear lack of high-quality data for recommendations, resulting in substantial variation in practice and frequent implementation of unsubstantiated interventions further highlights the need for a randomised controlled trial.7-10 The James Lind Alliance (JLA) Priority Setting Process in vascular wounds corroborated this by identifying SSI prevention as a top 10 research priority for both clinicians and patients.11 Similarly, the lower limb amputation process identified improvement of stump healing as a top priority.12

This survey aims to assess current practice and equipoise of UK vascular surgeons with potential interventions to prevent SSI in groin wounds and MLLA.

Method

Objectives

• To identify the current practice in the use of potential interventions to reduce SSI

• To evaluate the equipoise regarding potential interventions to reduce SSI in a multi-arm multi-stage (MAMS) trial

Study design

This was a national cross-sectional survey of UK vascular surgeons which was open for responses between 10 August 2023 and 30 September 2023. A Study Steering Committee (SSC) of four consultant vascular surgeons, three professors of surgery and four vascular trainees provided oversight and a consensus-based approach to survey development, validation and distribution. The design, conduct and report of this study follow the checklist for reporting of survey studies (CROSS) and the checklist for reporting results of internet E-surveys (CHERRIES).13,14

Questionnaire development

Using SSI prevention guidelines and a prior survey conducted by this group, potential interventions for evaluation in a randomised controlled trial to reduce SSI in MLLA or vascular groin incisions were proposed to the SSC.7-10 Initially two surveys were planned, one for MLLA and one for groin incisions. However, given the similarity in interventions and potential audience survey fatigue, the SSC advised that a combined survey addressing both patient groups would achieve optimal response rates. SSI prevention interventions were categorised as preoperative, perioperative and postoperative, dependent on the timing of administration in relation to the index procedure, and further classified according to their use for MLLA or groin incision. Questions were designed to follow Likert response options where possible with a combination of binary, multi-select and free-text options where required.

The SSC provided three rounds of internal validation following which, potential trial investigators provided final external validation. Questionnaire alterations were recorded as major (question added or removed) or minor (wording, syntax or response option modification). Twenty-nine SSI prevention interventions were initially proposed across both MLLA and groin pillars of the survey. The first internal validation round resulted in seven major (six questions removed, one added) and six minor alterations, the second internal validation round resulted in four major (zero questions removed, four added) and three minor alterations, whilst the final internal validation round yielded two major (zero questions removed, two added) and five minor alterations. No further alterations occurred following external validation.

The final survey included 54 questions; 26 related to interventions (14 MLLA, 12 groin), 24 assessing equipoise regarding randomisation (13 MLLA, 11 groin), two demographic questions and two individual questions regarding MLLA outcomes and willingness to recruit to the proposed trial. The final version of the survey is provided in Appendix 1 (online at www.jvsgbi.com).

Survey administration

The survey was designed and published using the QualtricsXM PlatformTM, Washington, USA. The survey was open to vascular surgery consultants and trainees from the UK and Ireland. Participants’ responses were invited through single-stage sampling of the members of the Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland (VSGBI), providing a representative model of the vascular surgical population. Survey distribution was primarily via email to the VSGBI membership with periodic reminders at two-week intervals, and pulsed dissemination from the @VascResearchUK twitter account. Further snowballing on social media was encouraged.

Participants completed the survey by following the anonymous study URL link or QR code. Multiple single participant responses were precluded using QualtricsXM options.

Statistical analysis

Responses were scrutinised by the SSC and non-response questionnaires removed. Partially completed questionnaires were included. Only responses submitted within the participation window were included in the analysis. Response data were exported to Microsoft Excel Version 16.79.1 for cleaning and analysis using IBM SPSS Statistics version 29.0.1.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York, USA). Demographic and Likert responses were reported as percentages of responses. Responses with >60% concurrent responses were taken as good levels of agreement and >80% similarly were considered excellent levels of agreement.

Results

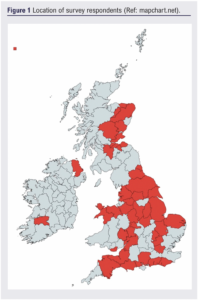

The survey received 58 responses from clinicians based in 38 NHS trusts/health boards in the UK and Ireland (Figure 1). Most of the respondents were consultant vascular surgeons (91%; 53/58). The other respondents were registrar level vascular trainees (7%; 5/58) and one physician associate.

Major lower limb amputation

Preoperative SSI prevention practices in MLLA

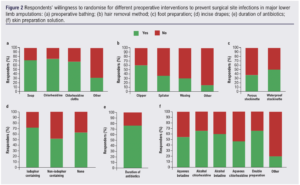

Most respondents do not routinely recommend a specific solution for preoperative bathing. When preoperative bathing was recommended, soap was the preferred cleansing solution (22%; 11/51), followed by chlorhexidine (13%; 7/54) and chlorhexidine cloths (2%; 1/49). Other cleansing solutions recommended included Octenisan and Stellisept (13%; 3/24). The majority of respondents would be willing to randomise patients to different preoperative bathing solutions (Figure 2a).

Clipping was always or often used for preoperative hair removal by 58% (33/57) of respondents. One responder each always used epilation/waxing. The majority of respondents (61%; 34/56) would be willing to randomise patients to hair removal with a hair clipper (Figure 2b).

Alcoholic chlorhexidine was always or often used for skin preparation by 68% (37/56) of respondents and alcoholic betadine was always or often used by 23% (11/48) of respondents. Aqueous betadine and aqueous chlorhexidine were infrequently used. In those who responded, a double preparation with any combination was always/often used by 41% (14/34) and sometimes used by 21% (7/34) of respondents. The most popular combination of double preparation was alcoholic chlorhexidine applied twice (33%; 3/9 respondents). The majority of respondents would be willing to recruit patients to a trial evaluating skin preparation with alcoholic chlorhexidine (67%; 37/55) and double skin preparation (67%; 37/55) (Figure 2f).

Preoperative prophylactic antibiotics were used by 76% (41/54) of respondents. The use and duration of postoperative prophylactic antibiotics was reported to be hugely variable. Over three-quarters of respondents (76%; 44/58) would be willing to recruit patients to a trial assessing the duration of postoperative prophylactic antibiotics (Figure 2e).

Incise drapes were never/rarely used by 67% (37/55) of respondents. The majority of respondents would be willing to recruit patients to a trial assessing the use of incise drapes (Figure 2d).

A waterproof stockinette was always/often used to prepare the foot during MLLA by 77% (44/57) of respondents. Willingness to recruit patients to randomised trials based on method of foot preparation is shown in Figure 2c.

Intraoperative SSI prevention practices in MLLA

An antimicrobial substrate to prevent infection in the surgical field during the procedure was never/rarely used by 82% (47/57) of respondents. Nearly three-quarters (72%; 42/58) of respondents would be willing to recruit patients to a trial evaluating intraoperative antimicrobial substrates.

Saline wound irrigation prior to closure was always/often undertaken by 47% (27/58) of respondents. Betadine and other irrigation fluids were rarely used. Most respondents would be willing to recruit patients to a trial assessing wound irrigation using betadine (69%; 40/58) and saline (79%; 46/58).

A drain was always/often inserted during MLLA by 59% (33/56) of respondents. Over half of respondents would be willing to recruit patients to a trial assessing insertion of a drain (58%; 33/57).

Only 4% (2/58) of respondents reported that they always/often change the instruments and 5% (3/58) of respondents reported they always/often changed their gloves prior to wound closure. The majority of respondents would be willing to recruit patients to a trial evaluating change of instruments (71%; 41/58) and a change of gloves (77%; 44/57) prior to wound closure.

The method of skin closure was variable. Continuous subcuticular sutures were always/often used by 70% (40/57) of respondents and interrupted sutures were sometimes used by 38% (22/58) of respondents. Skin clips were rarely/never used by 73% (41/56) of respondents, the majority of whom would be willing to recruit patients to a trial assessing continuous subcuticular sutures (69%; 40/58) and interrupted sutures (67%; 39/58) but not skin clips (47%; 27/57).

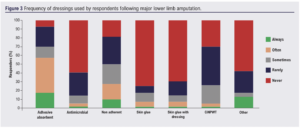

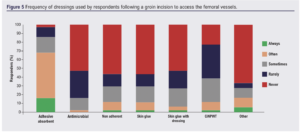

Popular types of dressing used to cover the wound post MLLA included adhesive absorbent dressings and non-adherent dressings (Figure 3). Skin glue and closed incisional negative pressure wound therapy (CiNPWT) were rarely used. Most respondents would be willing to recruit patients to a trial evaluating an adhesive absorbent dressing (71%; 41/58), antimicrobial dressing (71%; 41/58), non-adhesive dressing (74%; 42/57) and CiNPWT (74%; 42/57). Fewer were willing to recruit to the use of skin glue with a dressing (61%; 35/57) and skin glue without a dressing (54%; 31/57).

The majority of the respondents always/often used gauze, wool and crepe (62%; 36/58) or no stump dressing (34%; 18/54). Rigid stump dressings are rarely used (86%; 48/56). The majority of respondents would be willing to recruit patients to a trial using gauze, wool and crepe stump dressing (71%; 40/56), a rigid stump dressing (63%; 36/57) or no stump dressing (60%; 32/53).

Respondents were asked if there were any other interventions they felt should be considered. Responses included the use of absorbable sutures, blood glucose control, patient warming, preoperative optimisation, theatre environment (eg, laminar flow), nutritional assessment and optimisation, (non)-handling of skin edges and time the dressing is left undisturbed.

Vascular groin incisions

Preoperative SSI prevention practices

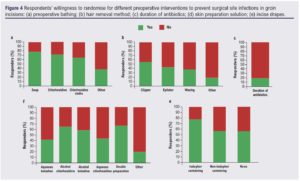

As with MLLA, respondents rarely recommended preoperative bathing prior to vascular surgery involving a groin incision. When preoperative bathing was recommended, soap was the most frequently recommended cleansing solution (25%; 11/44), followed by chlorhexidine (18%; 8/46). The majority of respondents would be willing to recruit patients to a trial investigating different preoperative bathing solutions (Figure 4).

Clippers were always/often used for hair removal prior to a vascular groin incision by 88% (40/45) of respondents. Epilation and waxing were never used by 98% of respondents (44/45). There was variability in the number of respondents willing to recruit patients to a trial assessing different methods of preoperative hair removal: clipping 57% (24/42), epilation (44%; 19/43) and waxing (40%; 17/43).

Alcoholic chlorhexidine was always/often used for skin preparation by 66% (29/44) of respondents. Alcoholic betadine (18%; 7/43), aqueous betadine (12%; 5/43) and aqueous chlorhexidine (9%; 4/42) were less frequently used. Double skin preparation was always/often performed by 26% (9/34) of respondents, and the combinations were variable. Respondents would be willing to recruit patients to a trial evaluating double preparation (67%; 29/43), alcoholic betadine (58%, 25/42) and alcoholic chlorhexidine (65%; 28/43) (Figure 4).

One preoperative dose of prophylactic antibiotic was always/often given by 93% (42/45) of respondents. Postoperative prophylactic antibiotics were given more variably. Postoperative prophylactic antibiotics were always/often given for 24 hours and for 48 hours by 38% (17/45) and 12% (6/48) of respondents, respectively. No respondents routinely gave prophylactic postoperative antibiotics for more than 48 hours. The majority of respondents (80%; 36/45) would not be willing to recruit patients to a trial of varying duration of prophylactic antibiotics.

Incise drapes were infrequently used by respondents. Non-iodophor drapes were always/often used by 9% (4/44) of respondents whilst iodophor-containing drapes were always/often used by 7% (3/44) of respondents. Respondents would be willing to recruit patients to a trial investigating iodophor-containing drapes (77%; 34/44), non-iodophor-containing drapes (58%; 25/43) or no incise drapes (58%; 23/40).

Intraoperative SSI prevention practices

Only 4% (2/44) of respondents always/often used an antimicrobial substrate in groin wounds. Respondents would be willing to recruit patients to a trial evaluating antimicrobial substrates (74%; 32/43).

Wound irrigation was always/often used by 16% (7/45) of respondents and saline was the most frequently used irrigation solution (11%; 5/45). The majority of respondents would be willing to recruit patients to a trial assessing wound irrigation with saline (74%; 31/44) or betadine (64%; 27/42).

A drain was always/often inserted by 36% (15/42) of respondents and rarely/never by 50% (21/42) respondents. Just over half of respondents would be willing to recruit patients to a trial investigating the impact of insertion of a drain (56%; 24/43).

The majority of respondents never/rarely changed their instruments (95%; 42/44) or gloves (91%; 41/45) prior to vascular groin wound closure. The majority of respondents would be willing to recruit patients to a trial evaluating a change of instruments (66%; 29/44) and a change of gloves (77%; 33/43) prior to wound closure.

Continuous subcuticular sutures were always/often used for skin closure by 92% (42/46) of respondents. The majority of respondents would be willing to recruit patients to a trial assessing continuous subcuticular sutures (70%; 30/43) or interrupted sutures (65%; 28/43), but less than half of respondents would be willing to recruit patients to a trial investigating skin clips (48%; 20/42).

For dressings, most respondents used an adhesive adherent dressing to cover the wound, with antimicrobial, non-adherent, skin glue and CiNPWT being less frequently used (Figure 5). The majority of respondents would be willing to recruit patients to a trial evaluating CiNPWT (83%; 34/41), adhesive absorbent dressings (74%; 32/43), non-adherent dressings (68%; 30/44) and antimicrobial dressings (66%; 29/44). Regarding skin glue, 64% (28/44) of respondents would be willing to recruit patients to a trial assessing skin glue with a dressing and 55% (24/44) to a trial of skin glue without a dressing.

Other interventions proposed by respondents included number of layers of closure, nutritional optimisation, type of diathermy and type of antibiotic used.

Future research

Nearly three quarters (72%; 42/58) of respondents strongly agreed/agreed that a combined outcome of SSI and wound dehiscence was an appropriate primary outcome measure in a trial investigating interventions to prevent SSI in MLLA and vascular groin incisions and were interested in recruiting participants to such a trial.

Discussion

There appears to be a plethora of practices used to reduce the risk of SSI for patients undergoing MLLA and groin incisions in vascular surgery in the UK. Despite the heterogeneity in practice, the survey found the majority of surgeons have clinical equipoise on the many interventions to reduce SSI, demonstrated by a high willingness to randomise for most of the proposed interventions. This is important information for trialists designing studies in this field.

This study found a lower use of certain interventions thought to reduce SSI compared with previous studies. In a survey of UK vascular healthcare professionals at a national vascular meeting regarding their use of impregnated incise drapes, antimicrobial substrates and dialkylcarbamoyl chloride (DACC) dressings in groin wounds in vascular surgery,15 over half of clinicians reported they used impregnated drapes (65%) and a third used antimicrobial substrates (32%). This is compared with only 13% and 4%, respectively, who always, often and sometimes use impregnated drapes and antimicrobial substrates in this study. The variation could be due to differences in survey structure. The current survey collected responses using a 5-point Likert scale whereas the previous survey used a dichotomous ‘yes or no’ response. Both surveys found similar results in terms of low DACC dressing use, a high level of equipoise/willingness to randomise to the proposed interventions and participate in randomised trials.

In a survey of SSI prevention practice in vascular surgery, which included 109 UK healthcare professionals, much higher numbers reported they did recommend practices such as preoperative bathing (67%), extended course of antibiotics beyond 48 hours (MLLA 74%, lower limb bypass 70%), antimicrobial substrates (72%) and CiNPWT (53%).10 Differences could be due to differences in the survey structure, but this does not account for all the variation.

This survey highlighted that, although the reported use of SSI prevention measures such as impregnated drapes, antibiotic duration and antimicrobial substrates is high, it does not necessarily mean that clinicians use them on every case and individual practice varies between procedures. There also appears to be recognition among clinicians that many SSI prevention interventions lack a supportive high-quality evidence base behind their use, leading to a willingness to randomise. Additionally, there is variation across the evidence base of interventions. Within groin incisions, for instance, ciNPWT appears to reduce SSI (moderate level of evidence) whereas locally placed antibiotics do not (low level of evidence).16 Some interventions exhibit a much greater cost profile than others, with varying degrees of efficacy. Stratification of patients using risk prediction models may yield greater results and personalised care.1 This information is valuable when designing a trial by informing potential interventions to test and understanding the likelihood of whether clinicians will recruit to the trial. This will help ensure a future trial is deliverable and does not waste resources. A multi-arm multi-stage (MAMS) trial design enables simultaneous or sequential evaluation of multiple interventions using robust methodology at a fraction of the cost and time of individual independent trials.17 Such a trial design would be well suited to the plethora of interventions and heterogeneity in evidence surveyed in this study.

The limitation of this survey is a low response rate. There are an estimated 376 vascular surgeons in the UK and Ireland, based on numbers registered with the VSGBI, giving the response rate of 15%. This could explain some of the variability in frequency of use of the interventions surveyed. An important consideration is that, within the months prior to dissemination of this survey, the VSGBI membership had received surveys on greener surgery and venous disease. The high volume of surveys in a short time frame may have contributed to ‘survey fatigue’ and the observed low response rate. Other reasons for a lower response rate include reach of the survey, whether only those who are actively engaged with the vascular community on X and the VSGBI email correspondence would have seen the survey, and the short data collection window. It is likely those who completed the survey are more interested in SSI prevention in vascular surgery. While this may not be representative of practice in the UK, it does provide an insight into potentially research active vascular centres to involve in a future randomized controlled trials.

Conclusion

This survey has highlighted, in those that responded, the frequency of use and willingness to randomise to various interventions to reduce SSI in patients undergoing MLLA and groin incisions in vascular surgery in the UK and Ireland. These results will inform the future trial design in this area to generate a high-quality evidence base for interventions to reduce the numbers of patients suffering an SSI after surgery.

Article DOI:

Journal Reference:

J.Vasc.Soc.G.B.Irel. 2024;3(2):76-83

Publication date:

February 29, 2024

Author Affiliations:

*Joint first authors

1. Centre for Clinical Sciences, Hull York Medical School, Hull, UK

2. South East Wales Vascular Network, Aneurin Bevan University Health Board, Royal Gwent Hospital, Newport, UK

3. Institute of Applied Health Research, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK

4. Department of Vascular Surgery, University of Bristol & North Bristol NHS Trust, Bristol, UK

Corresponding author:

Ross Lathan

Academic Vascular Surgical Unit, Hull Royal Infirmary, Hull,

HU3 2JZ, UK

Email: [email protected]