PROTOCOL

Changes in functional health status following open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair and the role of exercise-based rehabilitation: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis

Ravindhran B,1 Lathan R,1 Staniland T,2 Sidapra M,1 Carradice D,1 Chetter I,1 Smith G,1

Saxton J,3 Pymer S1

Plain English Summary

Why we are undertaking this work: The abdominal aorta is a major blood vessel which carries blood to the organs in the abdomen and measures 1.4–3 cm. An abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a balloon-like swelling of the aorta, which has a significant chance of rupturing if it grows beyond 5.5 cm. Consideration of AAA repair within 8 weeks is therefore recommended for all patients with aneurysms greater than 5.5 cm. Delayed recovery and complications are frequent following AAA repair. Complications include temporary or long-term damage to the lungs, kidneys and/or bowel. Reduction in functional status, likely due to bed rest and the demands of surgery, is also common. Currently, we do not know the extent of the decrease in functional status following AAA repair. In addition, exercise-based therapy following AAA repair could improve functional status, but we do not know if there is enough evidence to support this suggestion. We aim to identify how much functional status is reduced following AAA repair and whether it can be improved with exercise therapy.

What we will do: We plan to systematically review the evidence to improve our understanding of the reduction in functional status following AAA repair (component 1) and whether exercise can improve functional status (component 2) following AAA repair. We intend to search databases to identify trials that have explored the changes in physical function and the effect of exercise following AAA surgery.

What this means: This information will help us to understand just how much functional status is affected by surgery and whether exercise after surgery is helpful to improve it. If there is not enough information to find this out, this will help us to plan new studies.

Abstract

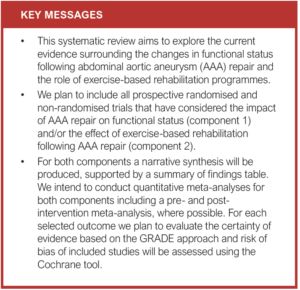

Background and objectives: The aim of this systematic review is to explore the current evidence surrounding the changes in functional status following open or endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) repair and the role of postoperative exercise-based rehabilitation programmes.

Methods: The proposed study will incorporate two separate systematic reviews within it, one to assess changes in functional status (component 1) and another to consider the role of exercise-based rehabilitation for improving functional status (component 2), both following AAA repair. The Medline, EMBASE and Cochrane CENTRAL databases will be searched using two separate search strategies including the terms “aortic aneurysm”, “functional capacity”, “functional decline” and” exercise therapy”. We plan to include all prospective randomised and non-randomised trials that have considered the impact of AAA repair on functional status and/or the effect of exercise-based rehabilitation following AAA repair. For component 1, the primary outcome will be changes in objective measures of functional capacity or physical function following AAA repair and, for component 2, it will be changes in physical function or functional capacity following exercise-based rehabilitation after AAA repair. The extracted data will include study characteristics – ie, sample size, a description of the intervention and control conditions (where applicable), outcome measures, length of follow-up and main findings related to outcome measures. For both components a narrative synthesis will be produced, supported by a summary table. We intend to conduct quantitative meta-analyses for both components. For each selected outcome we plan to evaluate the certainty of evidence based on the GRADE approach and risk of bias of included studies will be assessed using the Cochrane tool.

Conclusions: Based on a lack of current evidence, we present a protocol for a systematic review to investigate the functional changes associated with open and endovascular AAA repair and the potential value of postoperative exercise rehabilitation.

Introduction

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) repair may be associated with significant perioperative respiratory, cardiac, distal arterial or renal complications, which might necessitate a prolonged intensive care or hospital stay.1–3 In addition, patients with AAA are frequently elderly with widespread atherosclerosis, cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities.4-8 This, in combination with the fact that AAA repair is associated with significant perioperative metabolic and cardiopulmonary challenges,9,10 may mean that the required recovery, both in and out of hospital, has a significant and immediate impact on functional capacity, physical function and quality of life (QoL).

Indeed, systematic review evidence suggests that there are initial declines in both mental and physical domains of QoL following AAA repair, with the mental domains recovering to preoperative levels by 4–6 weeks, whilst the physical domains may take more than a year to recover.11,12 There is, however, no systematic review evidence considering the quantitative changes in functional capacity and physical function following AAA repair that are reflected in these reductions in physical QoL domains

Moreover, the evidence for postoperative exercise-based rehabilitation following AAA repair has not been synthesised, despite its potential to ameliorate some of these reductions in physical function and QoL. This is despite evidence to suggest that preoperative exercise programmes improve postoperative functional capacity and outcomes,13,14 and recommendations to enroll patients in exercise-based cardiovascular rehabilitation following major cardiac surgery.15

Therefore, the aims of this study are (1) to review the evidence considering quantitative changes in functional capacity and physical function following AAA repair; and (2) to review the evidence for postoperative exercise-based rehabilitation following AAA repair.

Methods

Protocol development

This protocol has been developed using the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions16 and is written in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocol extension (PRISMA-P).17 The PRISMA-P checklist is shown in Appendix 1 (online at www.jvsgbi.com). As we are encompassing two separate aims within this review, we plan to perform two separate systematic reviews which are outlined below.

Component 1: Considering quantitative changes in functional capacity and physical function following AAA repair

Search strategy and inclusion criteria

Searches will be performed using the MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane CENTRAL databases with no date restrictions applied.

In addition, trial registries such as clinicaltrials.gov and the Web of Science conference proceedings will be searched and authors of any identified ongoing studies or conference abstracts will be contacted to obtain study outcome reports where possible. Reference lists of any screened full texts or relevant systematic reviews will also be hand searched for other relevant papers. Only studies published in the English language will be included. Search terms will include “Aortic Aneurysm” [AND] “Functional Capacity” [OR] “Functional decline” [OR] “Functional capacity” [OR] “Aerobic endurance” [OR] “Functional Fitness”. A draft search is shown in Appendix 2 (online at www.jvsgbi.com).

We will include all prospective randomised and non-randomised trials that consider the impact of AAA surgery on quantitative measures of functional capacity and physical function. We plan to include participants aged 18 years and older, of either sex, who have undergone an elective open surgical repair or endovascular aneurysm repair, with results presented separately based on method of repair. We plan to include all types of AAA: infrarenal; juxtarenal; and suprarenal. To maximise available data, studies that include multiple surgical patient groups will be included if the data on the AAA subgroup can be obtained. Measures of physical function and functional capacity will include – but will not be limited to – cardiopulmonary exercise testing, the six-minute walk test, the short physical performance battery or its individual components and the timed up and go test.

Trial designs will include randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and observational cohort studies, but articles will only be included if measures are taken at baseline and following surgery to allow comparison. If studies include an intervention designed to reduce the impact of surgery on measures of physical function, these will only be included if data are available for a control group who did not receive an intervention.

Single-group, before-after studies will be included if the group did not receive an intervention designed to reduce the impact of AAA surgery on physical function. Studies that include other interventions, which are not likely to reduce the impact of AAA surgery on physical function, will be included.

Component 2: Considering the role of exercise-based rehabilitation following AAA repair

Search strategy and inclusion criteria

Searches will be performed using the same methods as those outlined above. However, search terms will include “Aortic Aneurysm” [AND] “Exercise therapy” [OR] “Physical Therapy” OR “rehabilitation”. A draft search is shown in Appendix 3 (online at www.jvsgbi.com).

We plan to include all prospective RCTs and non-randomised trials that consider the effect of exercise-based rehabilitation following AAA repair. Again, we plan to include participants aged 18 years and older, of either sex, who have undergone an elective open surgical repair or endovascular aneurysm repair. To maximise available data, studies that include multiple surgical patient groups will be included if the data on the AAA subgroup can be obtained. Rehabilitation may include supervised or unsupervised programmes but will only be considered exercise-based if they include some form of structured exercise training with regard to frequency, intensity and/or duration during the postoperative period. We plan to consider all exercise-based interventions either delivered in isolation or as part of a more comprehensive multimodal rehabilitation programme.

Data management, selection and collection process

For both components, search results will be uploaded and deduplicated using the specialised online review tool Covidence.18 Following this, titles and abstracts will be reviewed for eligibility by two independent reviewers (BR and RL). Full texts of these articles will be obtained and reviewed for inclusion. Any disagreement between reviewers will be resolved via discussion or by consensus with a third reviewer (SP). Information regarding search hits, number of duplicates removed, number of full texts reviewed, number of full texts excluded (with reasons) and number of studies included will be recorded for reporting in the PRISMA flow diagram. Where any full texts are not obtainable via conventional access methods, the authors will be approached to request the full article text.

Data extraction will then be performed by two independent reviewers using two separate bespoke designed spreadsheets, managed using a Microsoft Excel database (Microsoft, 2016, Redmond, WA, USA). The extracted data will include study characteristics including the sample size, a description of the intervention and control conditions (where applicable), outcome measures, length of follow-up and main findings related to outcome measures (a sample data extraction sheet is shown in Appendix 4, online at www.jvsgbi.com).

Outcome measures

For component 1, the primary outcome will be changes in objective measures of functional capacity and physical function following AAA repair. These measures will include – but will not be limited to – the ventilatory anaerobic threshold, peak oxygen consumption and ventilatory equivalents for carbon dioxide from cardiopulmonary exercise testing, the six-minute walk test, change in short physical performance battery scores and time taken for the timed up and go test. The changes in functional capacity and physical function at different time points following surgery will be collated and analysed as appropriate.

For component 2, the primary outcome will be changes in objective measures of functional capacity and physical function, including the measures outlined above, following exercise-based rehabilitation. For both components, secondary outcomes will include all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, event-free survival, rate of rehospitalisation, changes in QoL and adverse events related to the intervention. We also plan to include measures of frailty such as the modified frailty index and components of comprehensive geriatric assessment such as nutritional status, cognition and falls risk, if available. However, all relevant secondary outcomes will be considered and reported including compliance with exercise interventions.

Risk of bias and rating the quality of evidence

For both components, the risk of bias for each of the included studies will be independently assessed by two review authors using the criteria outlined in the revised Cochrane tool (ROB 2.0)19 (see Appendix 5, online at www.jvsgbi.com) or the ROBINS-I tool20 for non-randomised studies (see Appendix 6, online at www.jvsgbi.com). The relevant information will be extracted as outlined in the guidelines and each study will be either classified as having a ‘high risk’, ‘low risk’ or ‘some concerns’ of bias. In the case of ‘some concerns’ of bias, study authors will be contacted for more information. We also plan to include the overall predicted direction of bias for each outcome as outlined in the guidelines.16

For each selected outcome we plan to evaluate the certainty of evidence based on the GRADE approach, which includes five main domains: study limitations, imprecision, indirectness, inconsistency and publication bias. These domains will be used to upgrade or downgrade evidence after initial assessment. Based on these, we plan to categorise the quality of evidence as high, moderate, low or very low.21 We also plan to include a summary of the certainty of evidence and a quantitative synthesis of effects for each outcome.

Data analysis and synthesis

For component 1, the aim is to identify the impact of AAA repair on measures of functional capacity and physical function rather than to assess the impact of an intervention. Therefore, a narrative synthesis will be produced, outlining for each study the key characteristics and findings, supported by a summary of findings table.

For component 2, a similar narrative synthesis with a summary of findings table will be produced. In addition, if the included studies are sufficiently homogenous and include an intervention and control group, a meta-analysis will be carried out. This meta-analysis will provide a pooled estimate of the effect of a postoperative rehabilitation programme on various outcomes of interest. A quantitative analysis will be generated using Review Manager (RevMan version 5.3),22 which will allow for the creation of forest plots with an overall effect estimate and 95% confidence intervals. For this, we will use the reported post-intervention mean and standard deviation, unless only change scores are given. If the data reported are not suitable for entry into the meta-analyses, the authors will be contacted to obtain the required data.

The suitability of pooled analyses will be considered via interpretation of heterogeneity based on the I2 statistic and p value for the χ2 test. If significant heterogeneity is not present, data will be pooled using a fixed-effects model, with mean difference reported. If significant heterogeneity is present and the reason for it is not clear and explainable, then data will be pooled using a random-effects model, with standardised mean difference reported, which considers heterogeneity in the effect estimate. If the reason for significant heterogeneity is identifiable (ie, due to clear differences between interventions), data will not be pooled.

If meta-analyses are to be performed, sensitivity analyses will be carried out, removing trials of lower quality based on the risk of bias assessment and repeating the analyses. A minimal change in results would suggest that the analyses are robust.23 In the case that studies report both post-intervention scores and change scores from baseline, a further sensitivity analysis will be performed by using change scores instead of post-intervention scores, as has been recommended.24 If only post-intervention scores are reported in some studies, these will be used in conjunction with the change scores that are reported for the purpose of sensitivity analyses.

Discussion and conclusion

The possible complications and perioperative metabolic and cardiopulmonary challenges associated with AAA repair mean that the required recovery is likely to have a significant impact on physical function, functional capacity and QoL. Indeed, the former has been demonstrated in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting,25 but the evidence is yet to be evaluated in those undergoing AAA repair. QoL changes have been considered in those undergoing AAA repair, with significant reductions noted, which can take over a year to recover.12 Exercise-based rehabilitation has the potential to ameliorate some of these reductions in physical function, functional capacity and QoL. In addition, the objective of any AAA treatment is to prolong patient survival and maintain a QoL comparable to that of the general population, which can arguably be assisted by postoperative rehabilitation. However, the evidence for such interventions following AAA repair has not been considered, despite evidence to suggest that preoperative exercise programmes are beneficial in this population and the recommendation that all patients undergo cardiovascular rehabilitation following major cardiac surgery. Even if adequate evidence is obtained in this review to support the efficacy of exercise-based rehabilitation, barriers to exercise rehabilitation such as lack of funding, patient motivation and paucity of specialised physical therapists providing standardised exercise programmes will be pertinent.26,27 Given the limited evidence available, future research is urgently needed to explore ways to tackle these barriers in a patient cohort likely to achieve measurable benefit from exercise-based rehabilitation.

The anticipated limitation of this review is the possibility that there is little or limited evidence considering the areas of interest. Such a limitation has been identified in a recent review considering prehabilitation in a different vascular patient group.28

However, it is important to identify the current state of evidence on this topic to ensure that future research is accurately informed and appropriately designed to answer the intended question.

Article DOI:

Journal Reference:

J.Vasc.Soc.G.B.Irel. 2022;2(1):41-45

Publication date:

November 21, 2022

Author Affiliations:

1. Academic Vascular Surgical

Unit, Hull York Medical

School, Hull, UK

2. Hull University Teaching

Hospitals NHS Trust, Hull, UK

3. Department of Sport,

Health and Exercise Science,

University of Hull, UK

Corresponding author:

Bharadhwaj Ravindhran

Academic Vascular Surgical Unit,

Hull University Teaching

Hospitals NHS Trust, Hull,

HU3 2JZ, UK

Email: Bharadhwaj.Ravindhran

@nhs.net