ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Surgical Site Infection in Major Lower Limb Amputation (SIMBA): an international multicentre audit: baseline unit survey

The SIMBA Collaborative Group (in alphabetical order): Ismay Fabre,1 Brenig Gwilym,1 Louise Hitchman,2 Nina Al-Saadi,3 Lakna Harindi Alawattegama,3 Ian Chetter,2 Terry Hughes,4 Judith Long,2 Laura Magill,4 Thomas Pinkney,5 Matt Popplewell,5 Michael Wall,3 David C Bosanquet1

Plain English Summary

Plain English Summary Why we undertook the work: In 2022 over 3,000 people in the UK required an amputation of their leg. After amputation surgery there is a risk of wound infection. This can range from mild infections that can be treated with antibiotics to more serious problems including longer hospital stays, additional surgeries or even death. There are recommendations regarding prevention and treatment of wound infections; however, it remains unclear how effective these are and how closely hospitals follow this guidance.

What we did: We have designed an international audit: Surgical Site Infection in Major Lower Limb Amputation (SIMBA). Its aim is to evaluate infection rates, related complications and current care practices after amputation. As part of SIMBA, we conducted a survey to see how closely hospitals follow existing recommendations. It also looked to see which methods are most commonly used to prevent and treat wound infections.

What we found: We found that some practices were commonly used, such as using scans to plan surgery. However, there was significant variation in other areas. For example, not all hospitals routinely conduct pre-surgery assessments from specialists such as dieticians, psychologists and physiotherapists. Additionally, follow-up care, including rehabilitation and mental health support, varied widely between hospitals.

What this means: The results demonstrate that approaches to preventing wound infections after amputations vary and more specific evidence-based guidelines are needed. Better standardisation of practices could help to reduce infections and improve recovery for patients. More research focusing on amputation-specific guidelines could lead to better patient outcomes in the future.

Abstract

Introduction: Surgical site infection (SSI) is common after major lower limb amputation (MLLA) and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. National and international guidelines and a best practice pathway aim to optimise care and prevent complications, but adherence is unknown.

Methods: Surgical Site Infection in Major Lower Limb Amputation (SIMBA) is an international, prospective, collaborative audit which compared current practice against national and international recommendations and evaluated equipoise regarding best practice. Each participating centre completed a baseline unit survey containing Likert scale questions regarding local MLLA pathways. Responses were compared with the Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland’s best practice pathway, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Society of Vascular Surgery’s Practice management guide and the European Journal of Vascular Surgery’s Global Vascular Guidelines on the Management of Chronic Limb-Threatening Ischaemia guidelines.

Results: Forty centres (30 UK, 7 Europe, 2 Australasia and 1 Asia) completed the survey, yielding a response rate of 87% (40/46). MLLA was performed by vascular surgeons in all centres, with additional specialities also undertaking MLLA surgery including orthopaedic (n=10), plastic (n=4) and general surgery (n=3). Induction antibiotic prophylaxis was given in 32 (82.1%) of the centres. Prophylactic postoperative antibiotics were ‘commonly’ or ‘always’ given in 24 (61.5%) of the centres, typically comprising a 5-day intravenous course. Incise drapes were infrequently used (used ‘never’ for iodophor (39.5%, n=15) and non-iodophor (44.7%, n=17) containing drapes). Routine follow-up was conducted in 27 centres (69.2%) and preoperative vascular imaging was ‘commonly’ or ‘always’ performed in 37 centres (92.5%). Preoperative assessment by physiotherapists and/or occupational therapists and diabetic specialists occurred ‘commonly’ or ‘always’ in 32 (82.1%) and 27 (71.1%) centres, respectively. Dietetic and psychological assessment only occurred ‘commonly’ or ‘always’ in 8 (21.6%) and 9 (25%) centres, respectively.

Conclusions: This audit highlights the variability in practice, underscoring the need for consensus on best practice. Future studies should focus on generating high quality evidence to refine recommendations and reinforce adherence to guidelines to reduce SSI and improve outcomes after MLLA.

Introduction

Surgical site infections (SSIs) are a common complication following any surgical procedure, accounting for 20% of all hospital-associated infections.1 The incidence of SSI following major lower limb amputation (MLLA) is particularly high, with a recent systematic review reporting an overall incidence of 7.2% and single-centre studies reporting rates up to 27%.2 SSIs are a leading cause of in-hospital morbidity and mortality,3 and consequences of their development, including the substantial contribution to prolonged hospitalisation, result in SSIs being the costliest hospital-associated infection.1 Furthermore, SSIs post MLLA increase the risk of stump dehiscence and need for revision amputations to the same or a higher level.2 This may prevent a patient from independent ambulation,4 significantly affecting quality of life and negatively impacting mental health.5

The importance of this issue has been recognised by both clinicians and patients. The Priority Setting Partnership led by the Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland (VSBGI) in conjunction with the James Lind Alliance has highlighted improving wound healing and improving clinical outcomes after MLLA as two of the top 10 research priorities in amputation surgery.6 Furthermore, wound healing and stump infections have been highlighted in the core outcome set for MLLA.7 The VSGBI has established a best practice clinical care pathway designed to optimise quality of care and reduce complications after MLLA.8 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) have also published guidance relating to the prevention and treatment of SSI.3 However, the degree of adherence to these recommendations remains unclear. Various interventions, such as specialist dressings,9 negative pressure wound management systems10 and antimicrobial-coated sutures11 have become increasingly available. Benefits have been demonstrated from prolonged prophylactic antibiotic courses to reduce the incidence of SSI in MLLA;12,13 however, aside from this, evidence of effective interventions to reduce the incidence of SSI in MLLA is sparse, and all adjuncts incur additional costs, contributing to variability in practice.

Surgical Site Infection in Major Lower Limb Amputation (SIMBA) is an international collaborative audit comparing current practice against recommendations. It also aims to determine the incidence of SSIs and associated clinical sequelae, although these data are not part of this publication.14 The study consists of two parts: prospective data collection surrounding risk factors, interventions and outcome for patients undergoing MLLA, and an initial baseline unit survey completed once by each enrolled centre. This paper presents the results of the baseline unit survey. The primary aim of this survey was to assess adherence to published guidelines on reducing SSI. Secondary aims included assessing adherence to recommendations regarding optimising overall care and improving outcomes post MLLA, and evaluating equipoise regarding best practice for management of patients undergoing MLLA.

Methods

Study design

SIMBA is an international, prospective, collaborative audit designed to assess current clinical practice against established recommendations and to determine the incidence of SSI and associated clinical outcomes. A detailed protocol has been published in full.14 This audit is partially funded by the ROSSINI platform as part of the accelerator award scheme (Award ID: NIHR156728)15 and has been conducted in conjunction with the Birmingham Centre for Observational and Prospective Studies (BiCOPS) at the University of Birmingham. SIMBA is supported by the Vascular and Endovascular Research Network (VERN; https://vascular-research.net/), a multidisciplinary trainee-led vascular research collaborative.16

Centre enrolment began in October 2023, with data collection concluding on 1 May 2024. Any centre within the UK or internationally that provides emergency and/or elective MLLA under any speciality was eligible to participate. Centres were recruited through outreach by VERN using social media, email communications and professional networks. As part of the audit process, the lead consultant from each enrolled centre was required to complete a baseline unit survey detailing local pathways for managing patients undergoing MLLA.

Questionnaire development

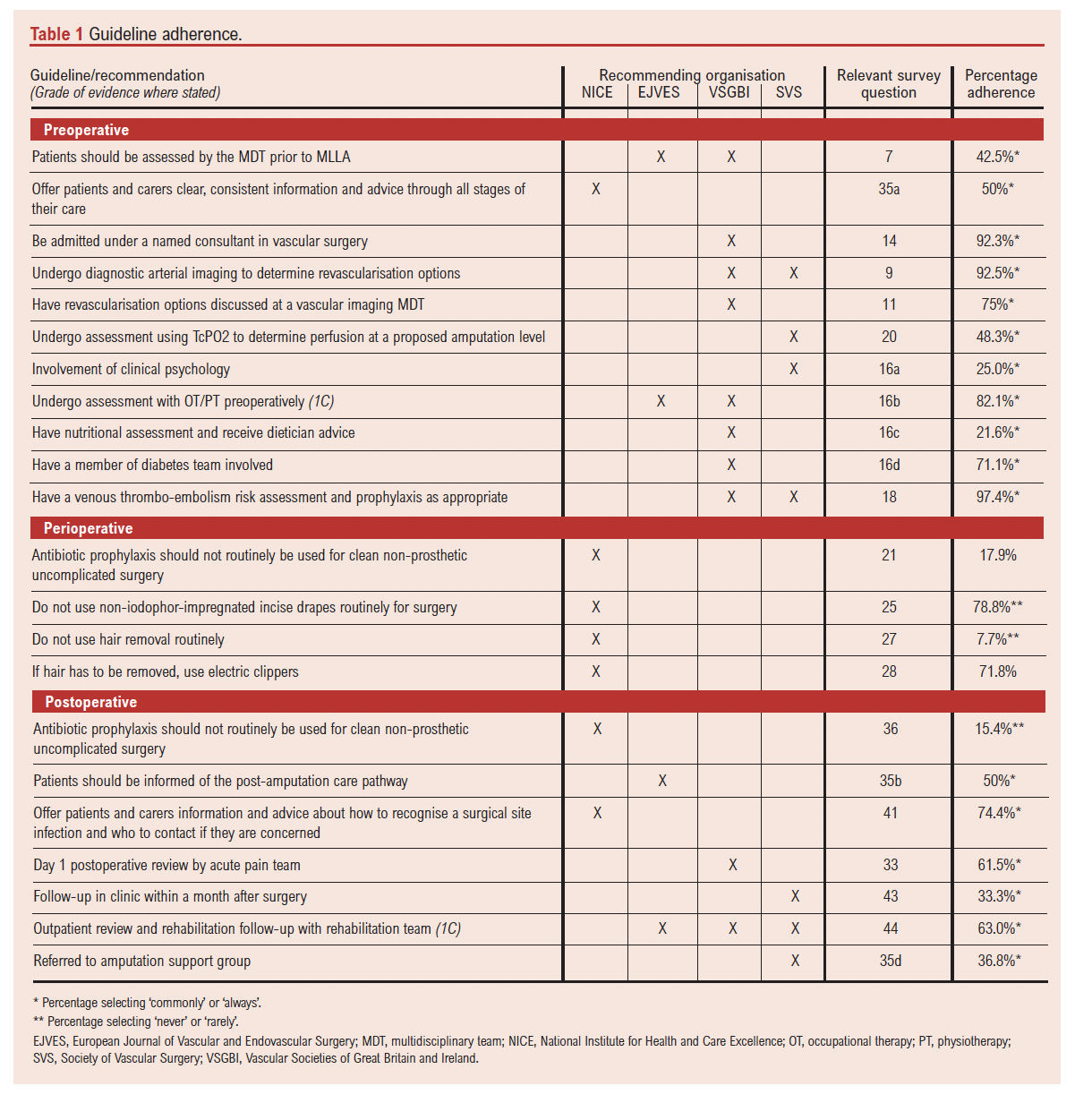

Strategies for SSI prevention and management detailed within the NICE guidelines and recommendations for the care of those undergoing MLLA, including those within the VSGBI Best Practice clinical care pathway,8 the European Journal of Vascular Surgery Global Vascular Guidelines on the Management of Chronic Limb-Threatening Ischaemia17 and the Society of Vascular Surgery’s Practice Management Guide,18 were identified and reviewed. Recommendations for preoperative, perioperative and postoperative care were included. Based on these recommendations, a cross-sectional survey was created, including questions designed to assess centre compliance (Table 1). Additionally, questions were incorporated to explore variations in practice and areas of uncertainty to evaluate equipoise on best practice. Responses were collected using a Likert scale where possible, with a combination of multi-select and free-text options where required.

The survey underwent two rounds of internal validation by the study management group. The survey was refined by consensus on major alterations (removing or adding questions) and minor alterations (wording or response modification). The first validation resulted in four major alterations (three questions added and one deleted) and five minor alterations, and the second yielded seven minor alterations.

The final survey included 29 questions; three were demographic questions, eight related to preoperative assessment and care, seven related to perioperative interventions and 11 assessed postoperative care and follow-up. The final version of the survey is provided in Appendix 1 online at www.jvsgbi.com.

Survey administration

The survey was built and published using the QualtricsXM PlatformTM and was distributed via an email to the consultant leads for all centres enrolled in the SIMBA audit. Participants completed the survey by following the study URL link. Non-responding centres were followed up with reminder emails. Where duplicate responses were received from a single centre, the most complete response was retained; if all responses were equally complete, the first submitted response was kept.

Statistical analysis and reporting

Responses were exported to Microsoft Excel for cleaning and analysis. Non-response questionnaires were removed. Partially completed questionnaires were included. Dichotomous and Likert responses were reported as percentage of responses, and multiple selection questions were analysed to find a median or modal average. The Checklist for Reporting Of Survey Studies (CROSS)19 was followed during all steps of the study and a completed checklist is provided in Appendix 2 online at www.jvsgbi.com.

As many of the guidelines and recommendations selected as audit standard were UK based, sensitivity analysis was also performed using only the UK centres.

Results

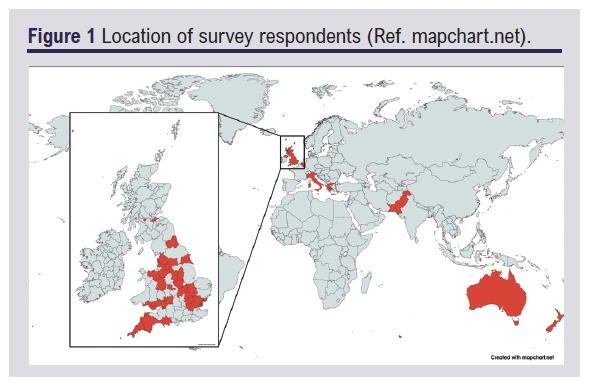

Of the 46 SIMBA centres, 40 completed the survey giving an overall response rate of 87%. This included 30/34 in the UK (88%), 7/9 European centres (78%), 2/2 Australasian centres and 1/1 Asian centre (Figure 1).

In all centres MLLA was performed by vascular surgeons. In 30.0% (12/40) other specialities were also performing MLLA, including orthopaedic surgery (n=10), general surgery (n=4) and plastic surgery (n=3). Patients were ‘commonly’ or ‘always’ admitted under a named consultant in vascular or orthopaedic surgery in 92.3% (36/39) of centres.

Adherence to published guidelines and recommendations varied across participating centres (Table 1). The grade of evidence supporting these recommendations was rarely specified. A sensitivity analysis including only UK-based centres demonstrated broadly similar results (see Supplementary Table 1 – Appendix 3 online at www.jvsgbi.com).

Adherence to SSI prevention and management guidelines

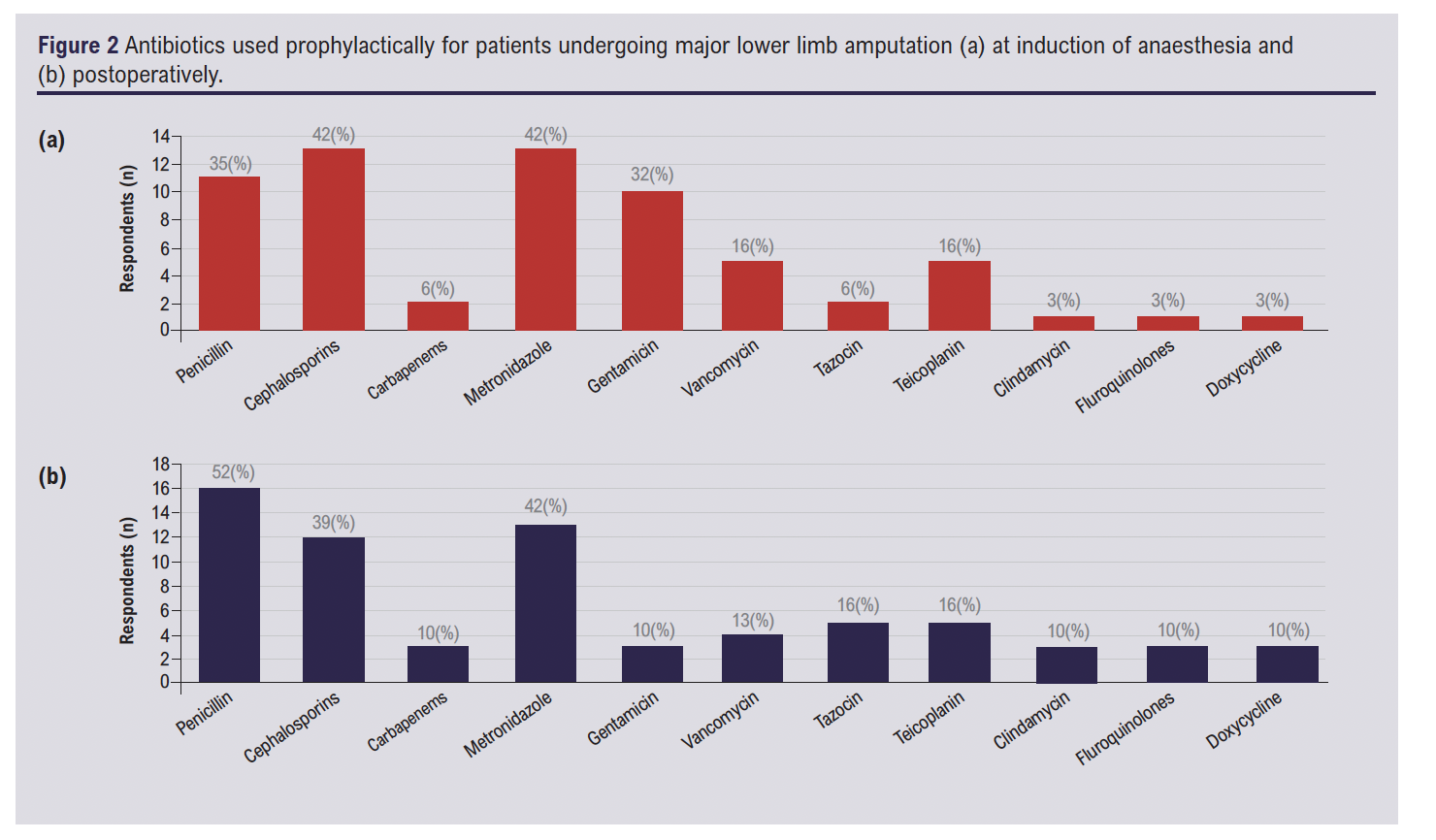

Antibiotic administration at the time of anaesthetic induction is routinely performed in 82.1% (32/39) of centres, with a median of two different antibiotics given intravenously. The most commonly used antibiotics are cephalosporins (13 centres) and metronidazole (13 centres) (see Figure 2a). Prophylactic postoperative antibiotics are ‘commonly’ or ‘always’ prescribed in 61.5% (24/39) of centres. The majority (22/24) administered exclusively intravenous antibiotics, whilst nine centres use either intravenous or oral routes and three centres routinely use oral antibiotics. Antibiotic choice varied between centres (see Figure 2b), with the most prevalent being penicillin (16/24), metronidazole (13/24) and cephalosporins (12/24) and the most common course duration ranging from 72 hours to 5 days. Adherence to the current NICE guidelines, which advise against the use of prophylactic antibiotics in clean, non-prosthetic, uncomplicated surgery, was low with 17.9% (7/39) of centres reporting they ‘never’ or ‘rarely’ administer antibiotics at induction and 15.4% (6/39) postoperatively.

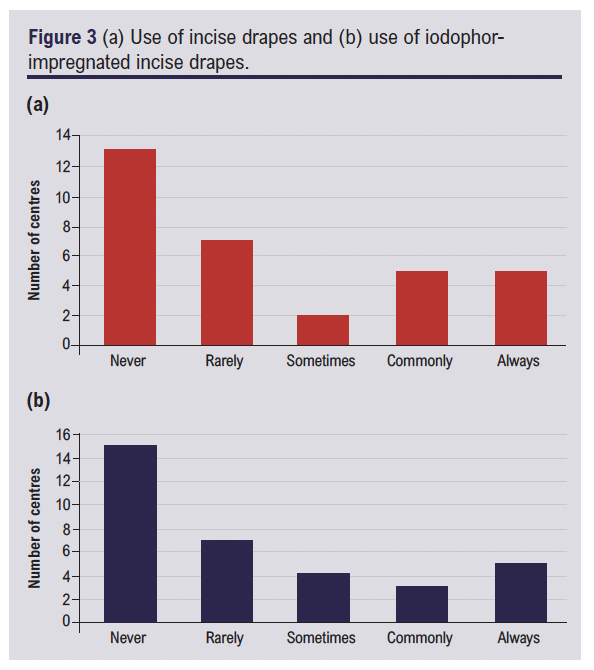

Routine preoperative hair removal is ‘commonly’ or ‘always’ performed in (24/39) of centres, with 71.8% of these using electric clippers aligning with guideline recommendations. However, only 7.7% (3/39) of centres reported ‘never’ or ‘rarely performing hair removal, reflecting low adherence to guidance advising against routine hair removal. Just over half of the centres (60%, 20/32) ‘commonly’ or ‘always’ perform MLLA without incise drapes. When used, 78.8% of centres reported ‘never’ or ‘rarely’ using non-iodophor impregnated drapes, reflecting good adherence with guidelines (see Figure 3a and b).

Adherence to guidelines on providing information about SSI recognition and management was high, with 74.4% (29/39) selecting ‘commonly’ or ‘always’ done. In comparison, leaflets detailing the procedure itself and expected postoperative recovery are ‘commonly’ or ‘always’ provided in 50% of centres (19/38).

Adherence to best practice clinical care recommendations

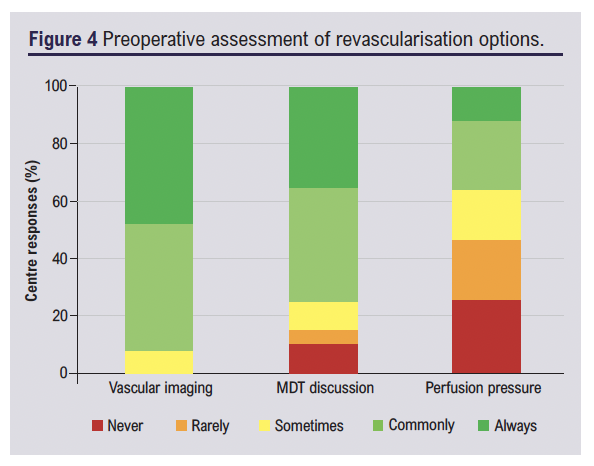

Diagnostic imaging to assess revascularisation options are ‘commonly’ or ‘always’ performed in 92.5% (37/40) of centres and 75% (30/40) routinely discuss these cases in vascular multidisciplinary meetings, demonstrating strong adherence to recommendations. In contrast, use of preoperative perfusion pressure measurements such as TcPO2 are only ‘commonly’ or ‘always’ implemented in 48.3% (14/29) of centres (Figure 4).

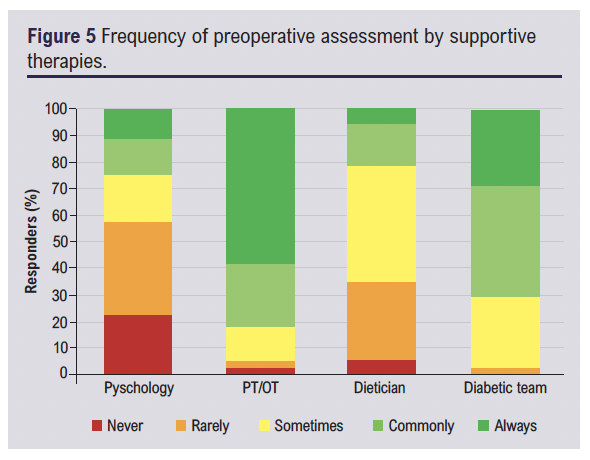

Routine preoperative assessment with occupational therapy and/or physiotherapy is ‘commonly’ or ‘always’ conducted in 82.1% (32/39) of centres and diabetic assessments are ‘commonly’ or ‘always’ undertaken in 71.1% (27/38), indicating good adherence to recommendations for multidisciplinary evaluation. However, adherence to guidelines recommending involvement of a dietician and clinical psychology were poor, with only 21.6% (8/37) and 25% (9/36) of centres selecting ‘commonly’ or ‘always’, respectively (Figure 5). Almost all centres (97.4%; 38/39) ‘commonly’ or ‘always’ implement thromboembolism risk assessment and prescribe prophylactic anticoagulation according to their local protocols.

In 61.5% (24/29) of centres, patients routinely receive input from the acute pain team on the first postoperative day, indicating moderate adherence to pain management recommendations.

Routine follow-up after MLLA is provided in 69.2% (27/39) of centres. Where routine follow-up was implemented, all centres (27/27) offered face-to-face appointments, with seven also offering telephone follow-up and two using video consultations. Follow-up is most commonly provided in consultant surgeon-led clinics (23/27), with 14 of these centres also offering a nurse-led and/or rehabilitation clinic follow-up. In four centres, follow-up is conducted solely in nurse-led clinics or by rehabilitation/artificial limb application clinic only, with no surgeon involvement. Overall, 63.0% had outpatient follow-up with the rehabilitation team, showing moderate compliance with recommendations. Adherence was notably low regarding referral to external (peer-to-peer) support groups such as the Limbless Association, with only 36.8% ‘commonly’ or ‘always’ offering this service.

Evaluating equipoise

Several domains of post-MLLA care demonstrated considerable variability. Marked differences were seen in the use of postoperative antibiotics, with 61.5% (24/39) of centres reporting routine use whilst 15.4% (6/39) reported that they ‘never’ or ‘rarely’ prescribe them. Among these, administration routes also varied with 91.7% (22/24) using intravenous antibiotics exclusively, 12.5% (3/24) using oral only, and 37.5% (9/24) reporting that they used either intravenous or oral depending on the case. Duration also varied with 12.5% (3/24) giving antibiotics for <24 hours, 29.2% (7/24) for 24–48 hours, 25% (6/24) for 48–72 hours, 50% (12/24) for 72 hours to 5 days and 58.3% (14/24) for >5 days.

Surgical skin preparation techniques also differed. Single skin preparation was ‘commonly’ or ‘always’ applied in 60.5% (23/38) of centres and double skin preparation in 33.3% (13/39), demonstrat-ing an area of clinical equipoise. Use on incise drapes also showed further disparity, with 40.6% (13/32) of centres always avoiding them whilst 31.3% (10/32) still used them ‘commonly’ or ‘always’.

Routine outpatient follow-up after MLLA was offered in 69.2% (27/39) of centres. Among these, 33.3% (9/27) occurred within 4–6 weeks, 33.3% (9/27) within the first month and the remainder at other time points. Format also differed: 85.2% (23/27) offered consultant-led review, 63.0% (17/27) included rehabilitation-led follow-up and 33.3% (9/27) offered nurse-led care. Notably, nine centres provided consultant-only follow-up while three relied solely on rehabilitation teams without surgical input. These variations high-light differing models of postoperative care delivery across centres.

Discussion

This audit provides insights into the current clinical practices surrounding MLLA and highlights the variability in adherence to current guidelines aimed at reducing SSI. The findings demonstrate that vascular surgeons are the primary specialists performing MLLA, although a notable proportion of centres also involved other specialities such as orthopaedics, general surgery and plastic surgery. The variability in parent speciality may reflect differences in surgical techniques, indication for procedures, patient demographics and subsequently risk factors for SSI development,20 likely contributing to variability in practice. However, this also raises important questions about the potential challenges in developing policies and/or best practice pathways to improve patient outcomes, particularly in the context of SSI prevention.

According to the 1964 wound classification, MLLA wounds are typically classed as ‘clean’,21 and therefore prophylactic antibiotics are not routinely recommended in the NICE guidelines. However, neither the guidelines nor this classification system account for the range of procedures, specialities, incision sites, patient cohorts and the subsequent variability in SSI risk.22 Many believe the increased risk of bacterial contamination secondary to ischaemic or infected tissue in MLLA warrants prophylactic antibiotic use,23,24 a consensus that seems in line with the survey results, with most centres (82.1%) administering induction antibiotics. Additionally, evidence suggests benefits of prophylactic postoperative antibiotics following MLLA,13,23 a practice also adopted in most centres (61.5%), although there was no clear consensus on duration of therapy. A recent randomised controlled trial13 published in 2022, three years after the 2019 NICE guidelines, demonstrated benefits of an extended 5-day course of antibiotic prophylaxis, highlighting how emerging evidence can surpass existing guidelines. It is important to consider that variation in antibiotic choice and administration route is expected due to differing local antimicrobial policies. This remains consistent with existing guidelines, which specify that, where antibiotics are indicated, selection should be guided by local antibiotic formularies, resistance patterns and microbiological tests where available.3 Given the risks of prolonged antibiotic use and antimicrobial resistance, it remains essential to balance antimicrobial stewardship with the prevention of infection.

The intraoperative practices and guideline adherence varied between centres. Hair removal was routinely performed in 61.5% of centres. However, the use of electric clippers, recommended over razors to minimise micro-abrasions, was not universal, with 25.6% of centres still employing razors often, which may increase the risk of SSIs.25 Current guidelines recommend using an alcohol-based solution of chlorhexidine but do not specify whether single versus double preparation should be employed. However, it is interesting to note the variability in local protocols, with 60.5% routinely using a single skin preparation and 33.3% often employing double skin preparation. There are some data from other surgical specialities demonstrating a reduction in bacterial colonisation with double preparation,26 including a randomised controlled trial of patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty which suggests that double preparation reduces SSI rates;27 however, these are not specific to MLLA. Some centres (21.1%) routinely use iodophor-containing incise drapes, which in other specialities have been shown to reduce SSIs;28 however, no studies have focused on MLLA and many centres commonly or always perform MLLA without the use of incise drapes.

The survey demonstrated widespread use of diagnostic imaging (92.5%) and multidisciplinary team (MDT) discussions (75%) to evaluate revascularisation options and suitability prior to MLLA. This is encouraging as vascular optimisation, when appropriate, reduces the rate of MLLA.29,30 Furthermore, imaging review and MDT discussion aid in the complex decision of selecting the appropriate amputation level, balancing functional outcomes against the risk of postoperative ischaemic wound breakdown. Recommendations advocate pre-procedural imaging and perfusion assessments; however, no single test is accepted as the gold standard to predict wound healing31 and the decision is often primarily based on clinical judgement.32 Whilst angiography is widely implemented, preoperative perfusion pressures such as TcPO2 are routinely used in less than half (48.3%) of centres, indicating a lack of standardisation. Perfusion pressures may be used to detect viable tissue for the amputation site. Studies suggest that TcPO2 values of >40 mmHg are associated with a higher percentage of successful healing whereas values of <20 mmHg may indicate an increased risk of non-healing.33 However, factors including limb oedema, cardiac output, smoking and pain can reduce accuracy, limiting its reliability as a sole determinant of amputation level. Consequently, there is no consensus regarding a specific threshold value. Despite this, the evidence suggests that perfusion pressures still provide valuable information.32 Additionally, emerging technologies such as machine learning algorithms may enhance risk prediction models by integrating patient risk factors and objective measurements. A recent pilot study demonstrated that machine learning incorporating multispectral wound imaging alongside patient risk factors improved the prediction for amputation wound healing.31 As these technologies evolve they may become an integral component of preoperative planning.

Occupational and physiotherapy assessments were widely implemented both preoperatively and postoperatively. Early assessment for rehabilitation can help prepare the patient physically and psychologically for rehabilitation,34 and evidence has shown us that early postoperative physiotherapy has a significant effect on function.35 However, fewer centres routinely engaged dieticians (21.6%) and psychiatrists (25%) preoperatively. This finding is concerning as malnutrition and psychological distress are risk factors for poor post-surgical recovery and SSI development.36,37 Recent studies have highlighted the potential value of integrated approaches such as enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) collaborative models38 and surgeon-physician co-management39 to ensure optimal prehabilitation and perioperative management,40 working towards better patient outcomes.

Follow-up varies significantly between centres, with almost one-third of centres (30.2%) not routinely providing routine follow-up after MLLA, which could lead to wound complications such as SSI and wound breakdown being under-diagnosed and therefore under-treated. Furthermore, less than half of centres routinely provide follow-up with a rehabilitation clinic (42.5%) or refer patients to external peer-to-peer support groups (36.8%) such as the Limbless Association. This lack of routine referral to support services may reflect under-appreciation of the role these resources play in long-term recovery and rehabilitation, given the significant physical and psychosocial impact MLLA often has. Greater integration of support services could improve patient outcomes and quality of life.41

Although this audit highlights significant variability in guideline adherence, it is important to note the limitations of the guidelines themselves. Some recommendations are outdated and others are derived from low-quality evidence,42,43 and recent trials have challenged existing guidelines such as the FALCON trial which questioned the superiority of chlorhexidine preparation in clean surgery.44,45 Notably, a recent study on diabetic foot disease reported similar findings, highlighting inconsistent adherence to guidelines and a lack of robust randomised controlled trial evidence supporting their foundation.46 More critically, the SSI prevention and management guidelines are designed for broader surgical contexts and do not specifically address MLLA. As a result, their applicability and effectiveness in this cohort are uncertain, given the risk of SSI is multifactorial, influenced by patient comorbidities, procedural techniques and perioperative care beyond the scope of current recommendations. Moreover, there is a lack of high-quality evidence supporting the efficacy of intervention ‘bundles’ (combinations of individually effective interventions) in reducing SSI rates when implemented concurrently.47 This audit also identified several areas of clinical equipoise, where significant variation in practice reflects a genuine lack of consensus of optimal management. Notably, the use of postoperative antibiotics showed great variability, with significant differences in route of administration and duration, ranging from 24 hours to >5 days. Similarly, intraoperative techniques such as single versus double skin preparation and the use of incise drapes showed substantial disparity between centres. Variability in preoperative MDT assessments and postoperative follow-up further reflected uncertainty in the holistic care aspect for those undergoing MLLA. This highlights the need for robust procedure-specific evidence to guide best practice in MLLA. Current works, including the ROSSINI-Platform trial designed to evaluate SSI prevention strategies across surgical specialities including MLLA,48 offer promising opportunities to continue addressing these evidence gaps. Furthermore, the European Society for Vascular Surgery is commissioning a Clinical Practice Guidelines specific for MLLA, set for publication in 2027.49

Study limitations

There are some limitations to this audit. The survey responses were self-reported, which may introduce recall or social desirability bias and affect the accuracy of reported adherence. However, the main SIMBA study includes prospective data collection, which will help validate these findings against actual clinical practice. Additionally, the survey was limited to centres that participated in the SIMBA audit, with an overall response rate of 87%. Non-responders included four UK sites and two European sites. This may have introduced response bias, and the relatively small sample size and geographical concentration within the UK may limit the generalisability of these findings. There are also some limitations in the survey design. The survey was designed and internally validated by the SIMBA study management group, composed primarily of vascular surgeons and researchers, without external validation or wider multidisciplinary input, which may have enhanced its comprehensiveness and applicability. As a result, some terms – for example, ‘MDT’ – may have been interpreted inconsistently. Additionally, we did not collect data on the availability of specific services (eg, psychology or rehabilitation services), which limits our ability to determine whether the absence of routine assessment reflects a lack of access or other factors such as surgical urgency. Similarly, the survey did not include qualitative fields or free-text options to explore reasons for ‘don’t know’ responses, which may reflect uncertainty or variation in terminology rather than true gaps in practice. Although some international guidelines were used, most recommendations assessed were based on UK-specific sources (eg, NICE and VSGBI), which may limit their applicability to international centres. Furthermore, while this audit provides a snapshot of current practice, it does not capture the real-time impact of these practices on SSI rates and patient outcomes. However, by evaluating adherence to established guidelines and identifying areas of clinical equipoise, this study highlights key areas for future research and focus points for future evidence-based guidelines tailored to this patient population.

Conclusion

This international multicentre audit highlights substantial variability in clinical practice and adherence to SSI prevention guidelines and best practice pathways in centres performing MLLA. Whilst there is good adherence to certain recommendations such as diagnostic imaging and multidisciplinary care, gaps remain, particularly in areas of preoperative nutritional and psychological evaluation, intraoperative standardisation and postoperative support. However, given the lack of specificity of guidelines and the multifactorial nature of the risk of SSI, a more tailored evidence-based approach is needed. Future research should prioritise high-quality procedure-specific studies to evaluate the impact of different perioperative strategies on reducing the risk of SSI. This will facilitate the development of standardised care pathways, ultimately improving clinical outcomes for patients undergoing MLLA.

Article DOI:

Journal Reference:

J.Vasc.Soc.G.B.Irel. 2025;Online ahead of publication

Publication date:

August 18, 2025

Author Affiliations:

1. South East Wales Vascular Network, University Hospital Wales, Heath Park Campus, Cardiff, UK

2. Hull University Teaching Hospital, Anlaby Road, Hull, UK

3. Black Country Vascular Network, Russell Hall Hospital, Dudley, UK

4. Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit, Park Grange, Birmingham, UK

5. University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, UK

Corresponding author:

Ismay Fabre, South East Wales Vascular Network, University Hospital Wales, Heath Park Campus, Cardiff, CF14 4YS, UK

Email: Ismay.Fabre3@ wales.nhs.uk