ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Bullying, undermining and harassment in vascular surgery training: a stubborn problem that damages the specialty

Marta J Madurska,1 Leanna Erete,2 Natalie Condie,3 Mimi Li,4 Ayoola Awopetu,5 Anna Murray,6 Shaneel R Patel,7 Iain N Roy,8 Hannah C Travers,9 Olivia McBride,10 Philip Stather,11 Rachael Forsythe,12 and on behalf of the Rouleaux Club, the UK Vascular Surgery Trainee Association

Plain English Summary

Why we undertook the work: Bullying, undermining and harassment (BUH) behaviours are present amongst healthcare workers and have detrimental effects on the victim’s well-being and may adversely affect patient outcomes. Although it is known that these problems are prevalent within surgery, there is little knowledge on the extent of the issue amongst UK vascular trainees specifically.

What we did: We carried out two surveys amongst vascular trainees in the UK to explore their experience with BUH at work.

What we found: We have shown that vascular trainees are continuing to experience BUH without evidence of improvement in the last few years.

What this means: BUH behaviours are ongoing problems faced by vascular trainees. Further research is required to more fully understand these issues and plan long-lasting interventions that will improve our workforce.

Abstract

Background: Bullying, undermining and harassment (BUH) behaviours are present amongst healthcare workers and have detrimental effects on the victim’s well-being and adversely affect patient outcomes. Although it is known that these problems are prevalent within surgery, there are few data on the extent of the issue amongst UK vascular trainees specifically.

Methods: The Rouleaux Club (RC), representing UK vascular trainees, has conducted two surveys which were distributed amongst 137 members of the RC between May and July 2017 and 831 between March and April 2021. Data were collected on demographics and personal experiences of BUH behaviours as well as those witnessed by trainees. Comparisons were made between the responses of each survey.

Results: The 2017 survey yielded 71 responses and the 2021 survey resulted in 86 responses, with estimated response rates of 51.8% and 10.3%, respectively. In 2017, 33 (47.1%) respondents reported personally experiencing BUH compared with 57 (72.2%) in 2021 (p=0.002). In 2017, seven (20%) reported witnessing BUH compared with 45 (57.7%) four years later. The most frequent perpetrators were vascular consultants (31 (81.6%) in 2017 and 55 (96.5%) in 2021, p= 0.020). BUH behaviours related to gender or sexual orientation increased from affecting two respondents (5%) in 2017 to 18 respondents (28.1%) in 2021 (p=0.004).

Conclusions: BUH behaviours are an ongoing problem within UK vascular training. Despite recent attempts to tackle these issues, there is no evidence of improvement and a signal for possible worsening of the problem. There is a need for further research to understand this issue in more detail in order to plan long-lasting interventions that will minimise detriment to individual trainees, protect the reputation of the specialty and maintain the safety of patients and optimal delivery of care.

Introduction

There has been growing recognition and concern related to workplace bullying, undermining and harassment (BUH) in the NHS. Although some overlap exists between BUH behaviours, they are well defined. Bullying is unwanted, offensive, intimidating, malicious or insulting behaviour related to an abuse or misuse of power towards a more vulnerable peer. Undermining is a behaviour that subverts, weakens or wears away confidence, and harassment is defined as unwanted conduct similar to bullying and undermining but related to a specific protected characteristic.1–3

BUH amongst healthcare workers can have a detrimental effect on the mental health of the victim, the training environment, as well as cause workforce attrition and result in lower standard of patient care.4–7 A safe training environment is paramount in medical training,8 yet a culture of bullying is reported to be a familiar setting to people working in the surgical field.9

Recent reports suggest that at least half of surgical trainees in the UK and abroad experience BUH.10–13 Unpublished data from a 2017 survey conducted by the Rouleaux Club (RC) (the UK vascular trainees’ association) demonstrated similar outcomes, prompting formal recognition of the issues by the Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland (VSGBI), General Medical Council (GMC) and the Joint Committee for Surgical Training (JCST).14,15 The RC has since repeated the trainee survey in 2021 to assess any changes in BUH in the UK vascular training environment.

The aim of this paper is to present the results of the 2017 and 2021 surveys with a view to analysing reported BUH behaviours in the UK vascular training environment.

Methods

The study was designed and conducted by members of the RC executive committee without any input from other organisations or professional bodies. The RC is the official UK vascular trainees’ association and aims to represent the views of trainees in vascular surgery in the UK and Ireland. It is free to join and has a current membership of about 1,000 participants including vascular trainees, non-NTN (National Training Number) registrar level doctors, core surgical trainees, foundation doctors as well as affiliate members including medical students interested in a career in vascular surgery, non-UK vascular trainees, vascular nurses and vascular scientists.

Multiple-choice and open-ended question surveys were designed and distributed to RC members in 2017 and 2021. The surveys were distributed electronically using SurveyMonkey® via a link sent in an email. The 2017 survey was sent out to 137 members with two email reminders between May and July 2017. The 2021 survey was sent to a total of 831 members with three email reminders following the initial email between March and April 2021. The 2021 survey was also distributed via social media (Twitter) with a link available to the public; the link was re-tweeted four times through March 2021. The survey responses were anonymised and voluntary. Completion of the survey was considered as implied consent for use of the data in the analysis. The 2017 survey was distributed to UK trainee doctors only while the 2021 survey was distributed amongst all members of the RC (including non-UK trainees).

Each survey provided definitions of BUH behaviours, confirmed respondent anonymity and highlighted the aims of the survey – to gain understanding of the experience or witnessing of BUH amongst trainees. Moreover, the 2021 survey highlighted the strategies put into place by the working group following the initial survey. The questionnaires differed slightly in their design. The surveys consisted of questions relating to demographics (age, gender, training level and grade) as well as BUH experience including personal experience and witnessing of BUH behaviours, types of behaviours, frequency, perpetrator role, level and specialty, experience and outcomes related to reporting of the negative behaviour. Additionally, data relating to perceptions of RC representation and support in case of BUH were also collected. The survey templates are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Data were stored using Microsoft Excel for Mac (Redmond, WA, USA). Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27 (Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical data were presented as percentages. Comparisons were performed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test if assumptions were not met. Graphical presentation of data was delivered using Prism 9 for macOS, version 9.3.1.

Results

Demographics

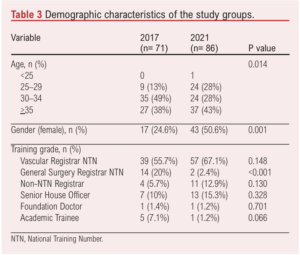

The survey conducted in 2017 had 71 respondents, and the survey in 2021 had 86 respondents, yielding a response rate of 51.8% and 10.3%, respectively. Demographic data are presented in Table 3. Due to the anonymous nature of the surveys, it was not possible to directly link responses from those who completed the surveys in both 2017 and 2021. In the 2017 survey, most (n=35; 49%) respondents were aged 30–34, while in the 2021 survey, most (n=37; 43%) were aged >35 years. In 2021, half (n=43) of the respondents were women compared to 24.6% (n=17) in 2017 (p=0.001). National training number (NTN) appointed vascular registrars formed 39 (55.7%) and 57 (67.1%) of the respondents for the 2017 and 2021 surveys, respectively (p=0.148), while only 4 (5.7%) and 11 (12.9%) non-NTN registrar level doctors (p=0.130) completed the surveys. General surgical trainees formed 20% (n=14) of the respondents in 2017 compared with only 2.4% (n=2) in 2021 (p<0.001).

BUH experience

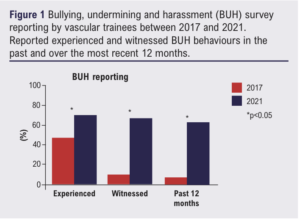

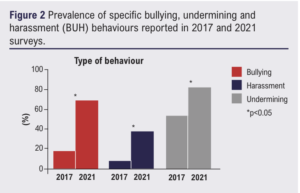

In 2017, 33 (47.1%) respondents personally experienced BUH behaviours compared with 57 (72.2%) in 2021 (p=0.002). In addition, seven (20%) reported witnessing someone else experiencing BUH behaviours in 2017 compared with 45 (57.7%) four years later (p<0.001; Figure 1). Of all the respondents, seven (9.9%) and three (3.5%) expressed that they did not want to say if they have experienced BUH in 2017 and 2021, respectively (p=0.097). Reported witnessing and experience of BUH behaviours within the last 12 months had increased from six respondents (23.1%) to 49 respondents (62.8%) between 2017 and 2021 (p<0.001; Figure 1). When categorising the specific type of behaviour, bullying was reported by seven (17.5%) respondents in the first survey compared with 41 (68.3%) in the second survey (p<0001); harassment was reported by three respondents (7.5%) compared with 22 (36.7%) in the two surveys (p<0.001); and undermining was reported by 21 (52.5%) in 2017 and 49 (81.7%) in 2021 (p<0.001; Figure 2). Outcomes relating to experience of BUH behaviours are shown in Table 4.

With regard to specific characteristics related to harassment, there was an increase in BUH related to gender and/or sexual orientation, from two respondents (5%) in 2017 to 18 respondents (28.1%) in 2021 (p=0.004). There were no differences between 2017 and 2021 in the reporting of other characteristics relating to BUH. Interestingly, 19 and three of the respondents in 2021 reported BUH related to academic training and less than full time training respectively, although these characteristics were not included in the 2017 survey.

When comparing gender differences in an overall cohort of both surveys combined, 27 (48.2%) women and 23 (30.8%) men reported having experienced BUH in the most recent 12 months or during their current placement (p=0.034). With regard to specific characteristics related to the negative behaviour, 17 women (28.8%) reported experiencing or witnessing harassment related to gender or sexual orientation compared with four men (4.3%) (p<0.001).

Perpetrator characteristics

Most of the perpetrators were reported to be doctors (according to 38 responses: 95% in both 2017 and 2021), within a consultant role (31 (81.6%) in 2017 vs 55 (96.5%) in 2021, p=0.020) in vascular surgery (Figure 3). With regard to the specialty of the perpetrator, 21 (55.3%) respondents reported that the BUH was perpetrated by a vascular surgeon in 2017 compared with 52 (89.7%) in 2021 (p<0.001), while other specialty doctors were reported to be perpetrators by eight (21.1%) and 22 respondents (38%) in 2017 and 2021, respectively (p=0.018; Table 4).

Raising concerns

If a concern was raised regarding BUH, only three (7.5%) and 10 (23.3%) respondents who either experienced or witnessed the behaviour felt that their complaint was taken seriously in 2017 and 2021, respectively. Furthermore, four (10%) responders in 2017 and six (14%) in 2021 felt that the victims’ welfare was appropriately addressed, and the perpetrator was appropriately treated. If experienced BUH in the future, only 39 (55%) of respondents in 2021 would be confident in reporting the incident to their educational supervisor, clinical supervisor, training programme director or other consultant colleagues within the team compared with 45 respondents (63.4%) in 2017 (p=0.018). Moreover, five (7%) respondents in 2017 and 26 (36.6%) respondents in 2021 expressed that they would not be confident reporting BUH to anyone.

Since the formation of the VSGBI BUH Working Group, 52 (73.2%) of the 2021 survey respondents were aware of the working group’s report published in 2018.15 Thirty (34.7%) respondents were aware of the BUH e-module offered by the Royal College of Surgeons in Edinburgh (RCSEd) with only 10 (13.9%) reporting that they had undertaken it. With regard to perceived changes in BUH reporting, 20 of the 2021 survey respondents felt that there was overall improvement, with 24 (33.3%) expressing improvement for reporting amongst trainees and nine (12.5%) for consultants.

Discussion

This is the first study to report longitudinal data on BUH behaviours experienced by vascular trainees in the UK. Our data suggest that, since the first survey in 2017 and despite strategies to address BUH behaviours, this may be an ongoing problem for our trainees. This study also provides a signal that BUH behaviours may indeed have worsened in the last four years.

BUH behaviours are not new in medicine and are not exclusive to the UK or to vascular surgery training. Survey data from the BMJ found that some 84% of junior doctors (of 1,000 respondents from a wide range of specialities) had experienced bullying behaviour in the past, and 70% had witnessed others being bullied.16 The GMC national training survey found that about one in 20 trainees reported bullying or undermining concerns. Whilst these data tell us that BUH behaviours affect trainees from all specialities, the problem has been highlighted repeatedly within surgical specialities and cannot be ignored. Our data compare with those reported by the Association of Surgeons in Training (ASiT) and the British Orthopaedic Trainees Association (BOTA), which included 1,412 surgical specialty trainees and found that 60% experienced or witnessed bullying or undermining, with 42% of these related to sexism. Similar to our findings, consultants were the most common perpetrators.11 Another survey by the RCSEd found that 40% of 250 respondents had experienced bullying, with surgical trainees being three times more likely to be bullied than other healthcare professionals.17 A recent study of US vascular trainees reported similar findings, with the most common perpetrator being a direct supervisor (48%).13 BUH behaviours also affect non-trainees. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists found that 44% of consultants are persistently undermined or bullied,18 whilst the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons found that almost half of its 3,516 members have experienced discrimination, bullying or sexual harassment, with consultants being the most frequent perpetrators.12 In another study from Australia including general surgical trainees and consultants, 47% of respondents had experienced bullying and 68% had witnessed bullying within the last year.19 A study from Greece found that about 50% of medical professionals have experienced abusive behaviour and a third of women surgeons experienced discrimination.10

BUH in healthcare harms not only the direct victim but ultimately affects patient care and can lead to poor outcomes.7 The individual at the receiving end of a negative behaviour may experience anxiety and depression which can eventually lead to substance abuse, burnout and suicide ideation.4,20,21 This in turn leads to absenteeism and long-term sickness, putting further pressure on an already strained service.22 A culture of BUH affects teamwork, where not only the victim but also witnesses are reluctant to speak up even when patient care is compromised.23 Furthermore, communication breakdown may take place leading to loss of situational awareness and loss of focus on the patient.24 Doctors who are victims of BUH are more likely to make mistakes at work and less likely to report patient safety issues.25

In response to the unpublished 2017 RC survey data, the VSGBI, vSAC and RC acted immediately to create a BUH Working Group with the specific aim to tackle these behaviours in vascular training. It is important to note that, whilst our longitudinal data suggest that the problems persist, the Working Group report was only published in 2019, leaving little time between publication and the second RC survey in 2021. It is likely that the strategies adopted and approved by the Working Group (including open admittance of the problem, specific supervisor training, introduction of a formal pathway for reporting BUH15) would not have taken effect within this timeframe and may not therefore be reflected in the results. In addition, the RCSEd BUH e-learning module was launched in 2017 with 471 people completing the module in 2018; however, uptake has declined steadily and only 67 people completed the module in 2021. Re-launch of the module with a particular focus on vascular surgeons could be considered.

The survey results differed in terms the respondent demographics. The 2017 survey included 14 (20%) general surgery NTN registrars while the subsequent survey only had two (2.4%) such respondents. These trainees were likely a cohort who entered training before vascular surgery became a separate specialty in 2013. Only 17 (24.6%) of the initial survey responders identified as women compared with 43 (50.6%) 4 years later. This may be accounted for by an increase in women vascular trainees over the past few years, although formal data on trainee demographics are not available. The disparity could also be due to responder bias if women have experienced/witnessed more BUH behaviours. The 2021 survey response rate is an estimate and much lower than the 2017 survey. After the 2017 survey the RC gained a presence on social media, leading to more members but also the possibility to disseminate the survey to the public via social media. It is not possible to deduce how many of the responses (if any at all) resulted from social media posts. Many new members after 2017 could have been affiliates (including medical students or non-UK trainee doctors). While the 2017 survey was disseminated amongst members who were UK-based doctors, the 2021 survey was sent out to all the RC members including those who were affiliated. This could explain a 10% response rate in the 2021 survey, although it is not known if the 90% who did not complete the 2021 survey experienced or witnessed bullying in a UK vascular training setting. It should also be recognised that the 2017 and 2021 surveys varied slightly with regard to several questions which may have had an impact on the validity of the study. When asking about specific characteristics related to the incident in 2017 the race/religion, gender/sexual orientation and all physical characteristics were grouped together, not allowing specific characteristics to be discerned. In 2021 all specific characters were included into a multiple-choice question and were more quantifiable. The results of the report of an incident in the 2021 survey considered whether the BUH stopped, but this was not considered in the earlier survey. Lastly, when asking who the trainee would feel comfortable speaking to if experiencing BUH in the future, the 2017 survey was open-ended while the 2021 survey specifically asked about the role of TPD and AES, reflecting the currently recommended channels for raising concerns.

This study has some other important limitations. An accurate response rate for the surveys cannot be calculated, as they were disseminated via public social media platforms as well as RC membership mailing lists. This also means that they would be accessible by people who are not UK vascular trainees. In addition, accurate contemporary data on trainee numbers and demographics with which to compare are not available. As the surveys were anonymous and voluntary, it was not possible to link individual responses to determine the scale of the change between timepoints. It is possible that trainees who have been affected by BUH may have been more likely to complete the surveys, introducing bias. These surveys were conducted as part of the RC end-of-year activities and the questionnaires were not validated. Importantly, the second survey coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, which has impacted the wellbeing of healthcare workers with reported increased anxiety, depression, stress and burnout.26-28 The effect of the pandemic on the second survey results is unknown, but it is clear that trainees have been affected by significantly reduced training cases during the pandemic,29 leading to concerns related to training progression. All of these may have had an influence on behaviours and perceptions reported in the 2021 survey and this is unaccounted for in our results.

Whilst our study suggests that BUH is a persistent problem in UK vascular training, further research is required to investigate the root causes of these issues more fully and objectively and to guide the next steps. Our non-validated survey data provide a signal, but we need robust and methodologically sound qualitative and quantitative research to clarify the scope of the problem. Thematic analysis of structured interviews may be one such approach, and the current close collaboration between trainee organisations and training bodies should certainly continue. The numerous resources already available should be highlighted again to the vascular community; an infographic guide for trainees experiencing BUH can be found in Appendices 1 and 2.

Conclusion

BUH behaviours continue to be a problem within UK vascular training despite recent strategies to tackle these. Our data suggest a signal that things have not improved and are possibly worse. There is a need to revisit the approach to addressing BUH in vascular training and to continue close collaboration amongst professional bodies.

Article DOI:

Journal Reference:

J.Vasc.Soc.G.B.Irel. 2022;2(1):9-16

Publication date:

November 21, 2022

Author Affiliations:

1. Sunderland Royal Hospital, Sunderland, UK

2. Royal Free Hospital, London, UK

3. Worcestershire Royal Hospital, Worcester, UK

4. Ipswich Hospital, East Suffolk & North Essex NHS Foundation Trust, UK

5. Basildon University Hospital, Mid and South Essex NHS Foundation Trust, UK

6. Birmingham Vascular Centre, University Hospitals Birmingham, UK

7. Liverpool University Hospitals, NHS Foundation Trust, UK

8. Molecular and Clinical Sciences Research Institute, St Georges University of London, London, UK

9. Department of Vascular Surgery, Ninewells Hospital, Dundee, UK

10. Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals, NHS Foundation Trust, UK

11. Edinburgh Vascular Unit, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

Corresponding author:

Marta J Madurska

Sunderland Royal Hospital, South Tyneside and Sunderland NHS Foundation Trust, Kayll Road, Sunderland, SR4 7TP, UK

Email: [email protected]