ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Can pre-existing CT or MRI scans be used to improve efficiency and ascertainment in the NHS Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening Programme (NAAASP)?

Tokede S, Kreckler S

Plain English Summary

Why we undertook the work: The NHS Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening Programme (NAAASP) invites men in the 12-month period in which they turn 65 for a one-time ultrasound scan of the abdominal aorta to check for the presence of an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). The abdominal aorta is the main blood vessel that runs from the heart down through the chest and abdomen. An AAA is a bulge or swelling in the aorta. Patients with AAA are often asymptomatic, but once the aneurysm ruptures, it is almost always fatal. NAAASP aims to detect AAAs in the early stage while they are smaller and less prone to rupture. There has been a reduction in the percentage of aneurysmal abdominal aortas detected by NAAASP over the last few years, reducing the cost-efficiency of the screening programme. Some men invited to the screening will have already had a previous 3D scan (eg, CT or MRI) for other reasons, which is sufficient to exclude an AAA for screening purposes.

What we did: We quantified the percentage of men invited to the Cambridgeshire NAAASP who had a previous CT or MRI scan (3D scans) with a suitable view of the abdominal aorta within each of the last six years prior to their NAAASP screening date.

What we found: Within our local screening programme we found that 7% of men have had a recent 3D scan with a view of the abdominal aorta within three years prior to their screening. This would reasonably be considered safe and sufficient to exclude an AAA for screening purposes. Additionally, some men who missed their appointment have also had a previous appropriate 3D scan within three years of their screening.

What this means: There is potential to increase the cost-effectiveness of the NAAASP by not inviting men with a recent 3D scan showing an aneurysm-free abdominal aorta for further imaging. In addition, identifying previous suitable 3D scans for men who do not attend their appointment confirms their aneurysm status without requiring a visit. While this does not change the screening uptake, it effectively improves the overall coverage of the eligible population.

Abstract

Background: The NHS Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening Programme (NAAASP) invites men in the 12-month period in which they turn 65 for a one-time ultrasound scan of the abdominal aorta to assess for the presence of an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). Detecting an asymptomatic AAA affords the opportunity to electively repair it before a potentially fatal rupture. However, there has been a reduction in the percentage of aneurysms detected by NAAASP over the last few years, reducing the cost-efficiency of the screening programme. It is hypothesised that a proportion of men may have pre-existing 3D imaging (eg, CT or MRI) of the abdomen undertaken for an alternative reason, which could be used to exclude an AAA. This may negate the need for a further dedicated screening scan with potential cost savings and improvement in ascertainment. This study aims to quantify the proportion of men in whom there exists satisfactory previous 3D imaging by examining a screened population invited to a single NAAASP centre. Potential cost savings and any impact on ascertainment will be estimated.

Methods: Records for 1000 consecutive patients invited to the NAAASP in Cambridgeshire between late 2022 and early 2023 were evaluated. After exclusions, imaging records for 694 were searched for previous CT or MRI scans within the last six years with an adequate view of the abdominal aorta. The first most recent suitable scan undertaken before the patient’s screening date was used, and any prior scans disregarded. Three years was considered a ‘safe’ retrospective period to screen out a normal aorta and be confident clinically of not missing a new aneurysm that had developed in the intervening period. However, we collected data on double this time span for the purposes of this project.

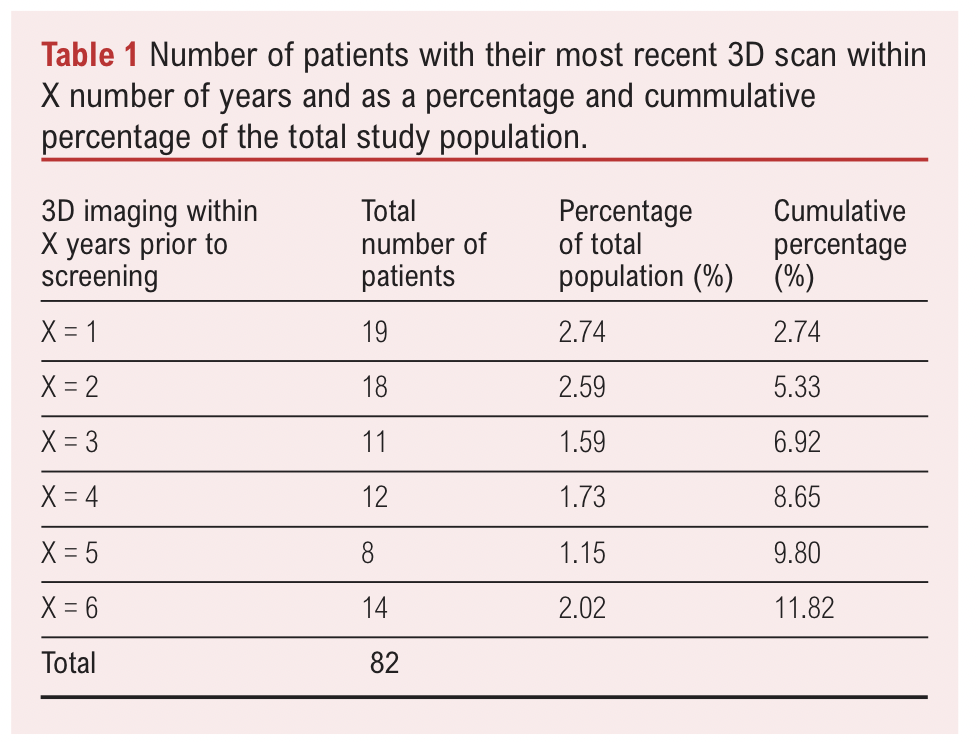

Results: 7% of the population had a pre-existing 3D scan sufficient to exclude an AAA undertaken within three years prior to their screening date and 12% within six years. This can be further broken down by the cumulative time interval as follows: within one year (n=19, 2.74%), within two years (n=37, 5.33%), within three years (n=48, 6.92%), within four years (n=60, 8.65%), within five years (n=68, 9.80%), within six years (n=82, 11.82%). By extrapolating our findings to the whole NAAASP cohort in Cambridgeshire for the year 2022–2023 (n=6703), we estimated the potential cost savings of ultrasound appointments saved for the NAAASP in Cambridgeshire if men with previous scans within three years were not invited for additional screening to be £17,046, equivalent to a reduction of approximately 464 screening appointments. Assuming a similar national distribution, we estimate potential national cost savings to be £800,819 in saved ultrasound slots if scans within three years were looked at.

Conclusion: 7% of men invited to the NAAASP have had previous 3D imaging sufficient to exclude an AAA within the last three years without additional imaging. These pre-existing data could be used to improve the cost-effectiveness of the screening programme and increase ascertainment.

Introduction

Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) are abnormal dilatations of the aorta below the diaphragm and before its bifurcation into the two common iliac arteries. The majority of AAAs are asymptomatic but, with time, the AAA grows and with it the chance of rupture, at which point it is often fatal.1 Early detection and monitoring improves patient outcomes by allowing an intervention to occur before the aneurysm reaches the point of rupture.2

The National Health Service (NHS) Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening Programme (NAAASP) is a nationwide screening programme in the UK that was fully implemented in 2013 with the aim of reducing death from AAA. The NAAASP invites men in the 12-month period in which they turn 65 for a one-time ultrasound scan of the abdominal aorta. Following screening, men with aneurysms measuring 3 cm or more are invited for follow-up surveillance scans, with aneurysms measuring 5.5 cm or more meeting the threshold for referral to vascular surgery.3

National screening programmes for AAA such as NAAASP have been shown to be cost-effective.4,5 But since the screening programme began, there has been a reduction in the prevalence of aneurysms detected. Reasons for this have been hypothesised, including an increased incidental detection rate (when a patient is scanned for a reason other than a suspected AAA) or the lowering of smoking rates, which is the biggest known modifiable risk factor for AAA development.5 Within the NAAASP there has been a reduction in the percentage of positive scans since the full implementation of the programme in 2013–2019 (from around 1.2% in 2013/14 to less than 0.8% in 2018/19).6 Furthermore, in the year 2022–2023 the aneurysm detection rate in the NAAASP fell to around 0.76%.7 The lower the detection rate or prevalence of AAA at screening, the less cost-effective the screening programme becomes.5

A possible way to increase the cost efficiency of the NAAASP would be to use pre-existing imaging (CT or MRI), where it exists, to screen out an AAA, negating the need for an additional dedicated NAAASP ultrasound scan. Such 3D imaging would need to be of adequate quality to fully visualise the abdominal aorta and contemporary enough to allay the concern that an AAA may have developed in the intervening period. In addition to potentially reducing the number of unnecessary screening scans, there is potential to mitigate the inefficiency of ‘Did Not Attend’ appointments. A percentage of men fail to attend their screening, wasting NHS time and money. Where prior 3D imaging exists, the health status of these men can still be determined without a visit. This effectively increases the overall ascertainment of the eligible population, ensuring safety even for those who do not engage with the traditional screening pathway. This is of importance as the number of men in the NAAASP is increasing but the prevalence of AAA detected at screening is not.7

Both CT and MRI have been shown to be adequate imaging modalities for the detection of AAA.8 Previously, the suitability of using previous CT scans done within a few years of ultrasound screening to retrospectively detect AAA in AAA-positive screened individuals was found to be highly sensitive and suitable for detecting AAA prior to ultrasound screening.9

The longer the period of time that passes between the prior 3D scan and the NAAASP screening date, the less confident one can be of a normal historical 3D scan, excluding a present-day AAA. Whilst no study has specifically evaluated this question, there are many studies of AAA growth rates in the literature.10–12 In a poll of 10 vascular consultants in our department, most would be confident that a normal 3D scan within the last three years would be sufficiently contemporary to negate the need for further screening. There is some support for this time frame from similar studies.9 For the purposes of the data collection for this study, we doubled this time frame to six years.

In this study we quantify the percentage of men invited to the NAAASP within our local programme with a suitable previous CT or MRI scan in each of the past six years. The results of this study could suggest ways in which the NAAASP could become more efficient and cost-effective in light of the changing epidemiology of AAA at screening.

Methods

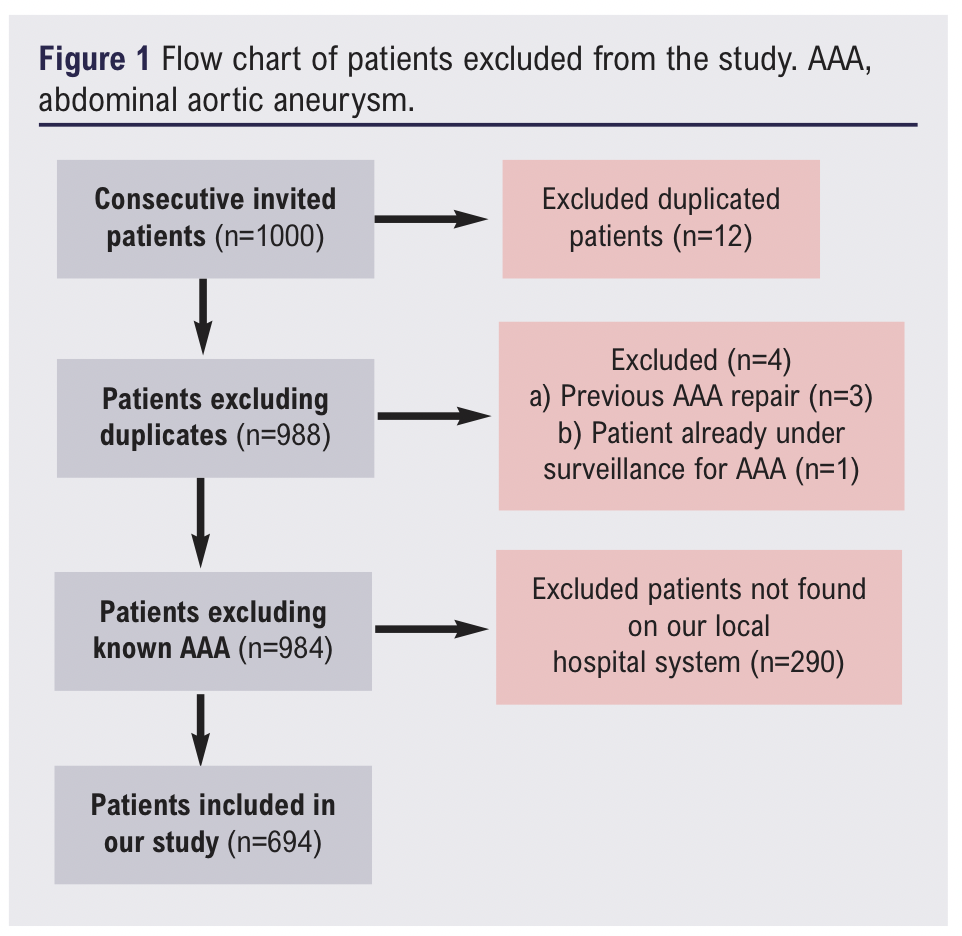

For this retrospective observational study we evaluated 1000 consecutive men invited to the NAAASP in the Cambridgeshire screening programme from late 2022 to 2023. Of these 1000 patients, duplicates and previously diagnosed AAAs were excluded. A number of patients did not have records in the local hospital system and were also excluded. This left 694 patients for evaluation (see Figure 1). Hospital radiology systems were interrogated to identify those men who had had a previous CT or MRI scan within the last six years of their NAAASP screening date. The actual imaging of these scans (not just the reports) was reviewed by a fourth-year medical student trained in aortic assessment. Measurements of the outer-to-outer diameter were taken on the axial view to confirm that the aorta could be visualised and that an AAA was not present. Abdominal ultrasound was not used as the aorta is not typically imaged for dedicated scans of other abdominal organ systems, recording of images is variable, and the operator dependency of this test makes it too subjective.

For patients with prior 3D scans, the date was compared with the NAAASP screening date to calculate the time interval. Only the most recent 3D scan performed prior to each patient’s screening attendance was documented; any additional prior scans were disregarded. For men who did not attend their screening appointment and therefore had no actual screening date, the date that screening would have taken place was used instead.

Results

Of 694 consecutive invited men, 82 (11.82%) had had at least one previous CT or MRI scan within the past six years, with the abdominal aorta visible and measurable (Table 1).

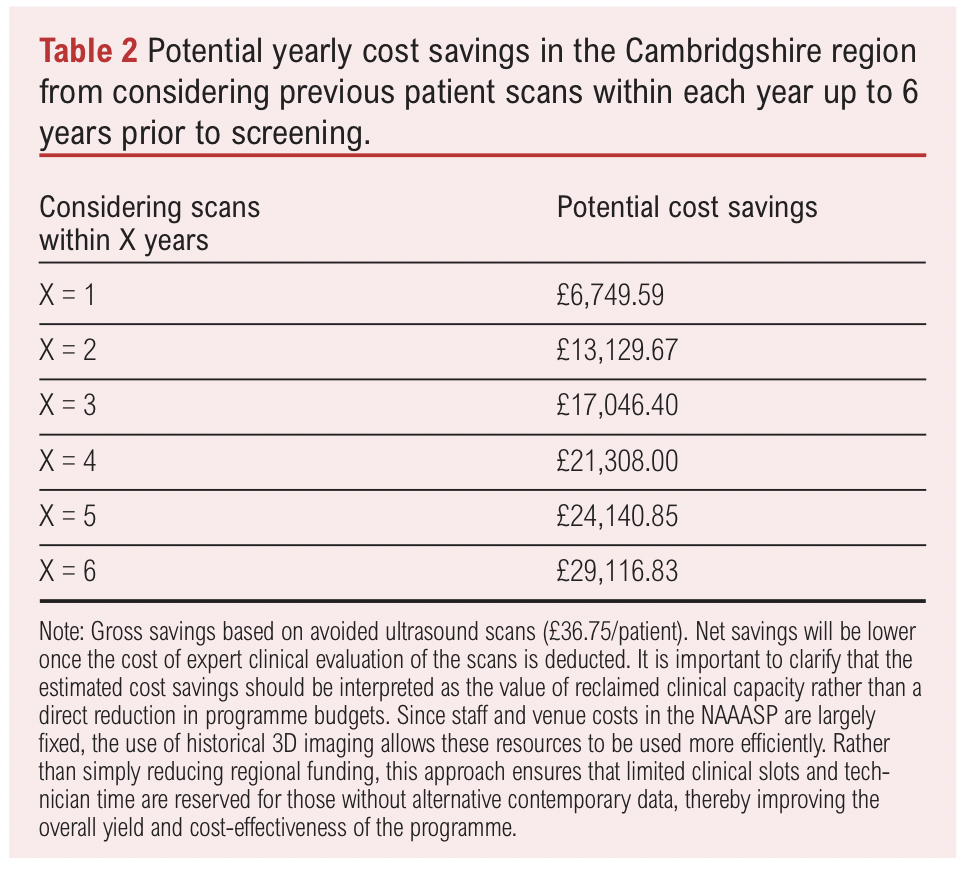

The cost of delivering the NAAASP programme was ascertained from NHS tariff data 2022–23. NHS tariff reimburses administrative costs (£1.93) and scanning costs (£36.75) on a per-patient basis (CUH local tariff reimbursement rate correct as of 2024). For the year 2022–2023 the local screening programme invited 6,703 men. We assumed that the administrative costs (£1.93) would not be saved as time would be required to look up the patient to check if they have had any previous 3D scan and to send out correspondence, whether a further scan is required or not. Estimated cost savings based strictly on the reduced number of ultrasound scans are shown in Table 2. In terms of operational workload, applying these prevalence rates to the total invited cohort of 6,703 men indicates a potential reduction of approximately 464 screening appointments annually if a three-year window is used for reviewing previous scans.

Discussion

To be satisfactory for the screening objective of excluding an AAA, imaging needs to be of sufficient quality and it needs to be sufficiently contemporary. In our cohort of 694 men invited for screening, 48 (7%) had a suitable CT or MRI scan within three years (Table 1). CT9 and MRI8 have proven sufficient sensitivity for excluding AAA. Three years was selected as a pragmatic time frame based on data of AAA growth and face validity from a local expert consensus. If a longer time frame is used, then the number of scanned individuals increases to around 10% at five years. However, this comes at the risk of missing new AAAs that have developed between time points. Further studies are required to evaluate what time frame between prior 3D imaging and the intended screening date could be confidently used within an acceptable envelope of risk.

Using scans within three years of the screening date would save around £17,000 per annum in ultrasound scans for the local Cambridgeshire NAAASP programme.

Beyond the financial implications, using pre-existing 3D scans within a three-year window would reduce the programme’s clinical workload by approximately 464 ultrasound appointments per year in the Cambridgeshire region alone. This reduction in appointment volume would release capacity within the screening programme and reduce the burden on clinical screening staff.

Nationally, in the year 1 April 2022 to 31 March 2023 approximately 314,900 men were offered AAA screening.7 Taking the cost of an abdominal ultrasound scan for AAA to be £36.75 and assuming the distribution of recent 3D scans nationally is the same as in our study cohort, approximately 21,791 men would have had a previous 3D scan within three years of their screening date. This equates to a national reduction of 21,791 screening appointments and £800,000 in saved ultrasound screening slots.

While these figures represent gross savings based on avoided ultrasound scan fees, we acknowledge that implementing this model involves a shift in labour costs. The administration time required to search for existing 3D imaging is anticipated to be cost-neutral as it can be performed within the existing time allocated for patient look-up and screening appointment booking. However, we recognise that a net saving must account for the clinical cost of an appropriately trained professional such as a radiologist to robustly evaluate and measure the aorta on prior 3D scans. As this study serves as a proof of concept, these estimated savings should be viewed as the value of reclaimed clinical capacity. By identifying men who do not require a physical appointment, programmes can optimise the use of physical scan slots and ensure that high-cost clinical resources are prioritised for those without alternative contemporary imaging.

Possible ways of implementing the results of this study

Implementing this in clinical practice requires a few steps:

1. Administrative search for prior suitable 3D imaging on a per-patient basis.

2. Trained assessment of 3D imaging and measurement of the maximal dimensions of the abdominal aorta.

3. Reporting the findings and inviting or excluding the patient from further screening.

Steps 1 and 3 can be performed by non-clinically trained personnel or may even possibly be automated in the future by a suitably trained AI algorithm. Step 2, however, requires an appropriately trained individual to accurately measure the abdominal aorta, although this also may potentially be deliverable by AI in the future. These steps have costs associated with them that, as mentioned, will likely reduce our previously estimated cost savings.

An alternative way in which this could be implemented would be to somehow mandate the reporting of aortic size in all 3D scans of all men aged over 60 years so that future searches could be conducted entirely by non-clinically trained individuals. This, however, has its own associated cost and, in practical terms, it would be near impossible to guarantee 100% compliance from reporters.

One way the findings of this study can be immediately implemented in the clinical setting (and indeed this is something that is being piloted in Cambridgeshire) is to search for prior 3D imaging for patients who did not attend their first screening appointment. This can be done by the screener in the ‘lost time’ during the did not attend appointment. Where this is found, the screening appointment is not consequently wasted and the ascertainment is improved. This does, however, require an amount of additional subsequent input from a clinically trained staff member to evaluate the 3D scan.

Study limitations

A limitation of this study was the small sample size of 694 men and also the fact that these men were all within a single geographical region. 3D imaging rates may vary around the country, which may make our findings more or less applicable when extrapolated to a national cohort.

How far back in time to accept a 3D scan to confidently exclude an AAA today is uncertain. Based on a focused discussion with 10 UK vascular consultants, three years was considered an acceptable limit, giving face-validity to our methodology. Beyond this, there was less confidence in the reliability of historical scans. This tallies with the limited available literature.9 Further studies are required to evaluate the reliability of historical scans to exclude a contemporary AAA and to consider how old is too old to reliably exclude an AAA.

Conclusion

Pre-existing 3D scans may be used to adequately screen for AAA in 7% of the population, obviating the need for an additional dedicated ultrasound scan. If this data can be identified and evaluated in a cost-effective manner, then this could result in cost savings for the NAAASP. Use of this data would also increase the coverage rate by screening men who would otherwise not attend.

Article DOI:

Journal Reference:

J.Vasc.Soc.G.B.Irel. 2026;ONLINE AHEAD OF PUBLICATION

Publication date:

February 20, 2026

Author Affiliations:

Cambridge University Hospitals

NHS Foundation Trust,

Cambridge, UK

Corresponding author:

Dr Sinmiloluwa Tokede

Trinity College,

Cambridge

CB2 1TQ, UK